On the night he cut a deal with the FBI, Guy Gentile was on his way to a Connecticut casino for his cousin’s bachelor party. He’d jetted up from the Bahamas, where he was running an online stock brokerage that cleared a million dollars a year without much effort on his part. Then 36, he was a working-class kid who’d finagled his way into the dicier edges of finance, and he dressed the part, with neatly trimmed stubble, designer jeans, a silver Rolex, and sunglasses that hung from the collar of his tight T-shirt, just below a few tufts of chest hair.

Gentile was feeling edgy about traveling stateside. It was July 2012, and regulators had been making calls about a stock play he’d been involved with a few years earlier. He’d been part of a group that the FBI suspected had suckered investors out of more than $15 million by manipulating the market for shares in a Mexican gold mine and a natural gas project in Kentucky.

As Gentile’s plane landed in White Plains, N.Y., he saw the flashing lights of police cars on the tarmac, confirming his fears. Before passengers could disembark, uniformed men came on board. Gentile dialed his lawyer, but the men grabbed the phone out of his hands, handcuffed him, and marched him off the plane.

Soon, two FBI agents picked him up from an airport detention room and drove him to a neon-lit diner in Newark, N.J., near their office. They bought Gentile a bacon cheeseburger and a Diet Coke and told him he had two options: Either they could throw him in jail, seize his assets, and hand his case to a prosecutor with a 95 percent win rate, or he could help them catch a bigger fish—and maybe make his problems go away. Gentile didn’t need to think it over. Whatever you want, he said, I’ll do it.

Normally the identity of an FBI cooperator would be kept secret, but sometime last year, a website called Rogue Informant went live. It bore the tagline “They said he had ice flowing through his veins,” a picture of a man getting off a private jet, and no identifying information. A trader told me who was behind it.

When I called Gentile, it was as though he’d been waiting for me. He said he had an amazing story to tell, promising that it included celebrities and a government coverup. “Remember the movie American Hustle? It’s kind of like that, with way more dirt and twists and f---ed-up shit,” he said.

He told me that the information he’d gathered across three years had led to dozens of arrests and helped prevent hundreds of millions of dollars in potential fraud losses. That made sense, in a way. Most stock market scams are easy to spot but hard to prove—even promoters of the most dubious schemes can operate for years, taking advantage of legal loopholes, offshore hideouts, and anonymous shell corporations. Yet the Department of Justice often claims in its press releases that since fiscal 2009 it has “filed over 18,000 financial fraud cases against more than 25,000 defendants.” Gentile offered a rare chance to see how the FBI is making these cases—even though, if his website is any indication, something went dramatically wrong.

I met Gentile at his office in Carmel, N.Y., a quiet suburb about an hour’s drive north of Manhattan. It was one of the hottest days of the summer, but there was no air conditioning because he’d stopped paying his utility bills. Now 40, Gentile was about to turn the building over to his estranged wife in their divorce. His office was a shrine to rags-to-rich-douchebag movies. On one wall was a poster of Al Pacino as Scarface and another of Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street. DVDs of the latter and American Hustle were stacked on a side table. “The whole experience was very surreal. I felt like an actor in a movie,” Gentile said of his work with the FBI.

We decided to find someplace less broiling to talk. In his red SUV, he put on a techno version of the James Bond theme and puffed mint-infused smoke from a vape pen. A Make America Great Again hat lay on the dashboard. As we drove, he launched into his story.

Gentile is the son of Italian immigrants. His father ran a gardening business in Mount Vernon, N.Y., and his mother worked in a sprinkler-head factory. Gentile spent his summers pulling weeds and mowing lawns; when he was old enough, he started working nights at a pizzeria. (He met his future wife there, after she left him a note while he was out on a delivery, telling him he was cute.) He was an indifferent student, more interested in making money and spending it on his silver 1985 Monte Carlo, which he fitted with a nitrous-oxide injection system and drag-raced at a track in New Jersey. He considered becoming a police officer after graduating from high school, but instead took a job as a syrup quality-control inspector at a Coca-Cola plant.

He discovered day trading in 1997, not long after E*Trade began offering the service online. A flood of websites and message boards popped up to give investors advice. Even punk rock legend Joey Ramone was giving stock tips. Gentile started his own subscription service, called DayTraderPro. For $35 a month, investors could get tips (“Don’t attempt to buy the bottom or sell the top. Wait and see which way it’s going”) and watch a live feed of a “professional” investor’s trades. The advice was basically worthless, but Gentile got in the game early enough to attract a small following. His computer would ping every few minutes to announce a new subscriber, according to Arthur Quintero, a compliance consultant who worked with him at the time.

In 1998, Gentile quit his job at Coke. He created his own trading website, an E*Trade knockoff that collected fees for executing trades. His clients weren’t getting rich, but it didn’t hurt his bottom line: By 2009 that company and another trading firm he’d started were netting about $3.5 million combined. Gentile drove Ferraris and Lamborghinis, including a white convertible that a dealer told him had belonged to R. Kelly, and invested in a Miami reggae record label. He referred to his lifestyle as that of a “simple jet-setter.”

After the dot-com bubble burst, U.S. regulators began implementing rules to protect clueless investors from themselves, such as requiring that day traders have at least $25,000 to their names and banning funding accounts with credit cards. With the number of prospective clients declining, Gentile decided to move somewhere with fewer regulations. He set up shop in the Bahamas in November 2011. Brokers there don’t have to follow day-trading rules, and they can take American customers as long as they don’t advertise for them.

The loophole gave Gentile a steady stream of business, and the offshore brokerage basically ran itself. Bored and still daydreaming about a law enforcement career, he signed up to get an online associate degree in criminal justice from the University of Phoenix and registered as a freelance bail enforcement agent with the state of Connecticut. But before he had a chance to track down any fugitives, he boarded the flight to White Plains, and the FBI presented him with a better chance to live out his fantasies.

At the diner in Newark, the FBI accused Gentile of participating in a pump-and-dump con that’s as old as the stock market. Promoters take over a worthless shell company, announce that they’ve found a promising venture, and send out a glossy marketing brochure to thousands of potential suckers. Some investors are gullible enough to buy the whole story, while others suspect the con but think they can get in and out quickly enough to profit. Once the frenzy dies down, the stock is almost worthless and the promoters move on to their next scheme. The government had trading records showing that while Gentile was running his U.S. online brokerage, he’d promoted the Mexican gold mine and the Kentucky gas-drilling project, then dumped millions of shares at near-peak value.

Gentile maintains that he did nothing wrong. But rather than try his luck in court, he became one of the FBI’s 15,000 informants, or “confidential human sources,” as the bureau calls them. The FBI has been using this tactic against stockbrokers and fund managers since at least 1992, when it created its first squad dedicated to Wall Street crime after the case against junk-bond king Michael Milken brought securities fraud into the mainstream. Informants are crucial to these cases, because tape recordings demonstrating wrongdoing cut through the complexity of stock market schemes for juries. And unlike agents, informants don’t require warrants to elicit evidence. Turncoats have driven some of the FBI’s biggest Wall Street investigations, like the landmark insider-trading cases against Raj Rajaratnam and Steve Cohen’s SAC Capital Advisors.

The day Gentile was arrested, the FBI agents who nabbed him had their eye on a lawyer named Adam Gottbetter. A regular on the Manhattan charity circuit, with a $12 million condo on the Upper East Side and an office on Madison Avenue, Gottbetter was by all appearances a Wall Street aristocrat. He favored tailored suits and kept his curly hair slicked back, flew to the Hamptons on private jets, and played in a dad band at fundraisers for the elite all-girls Spence School. Gottbetter pitched himself as an expert at taking small companies public, but the FBI suspected that he actually specialized in arranging crooked stock deals.

The dozens of companies in regulatory filings that mention Gottbetter’s name generally show the same pattern: A long-dormant stock spikes, then drops toward zero. By my calculations, during the time Gottbetter was listed in the filings, the companies’ peak market value was $5 billion more than their collective worth now. The FBI had identified this pattern, but it needed Gentile to nail Gottbetter. The pair had worked together on the natural gas play starting in 2007. The agents wanted Gentile to get back in touch with Gottbetter and coax him into saying on tape that he’d committed a crime.

After the talk at the diner, Gentile spent the night in jail. The next day he and his lawyer sat down with an assistant U.S. attorney for New Jersey. Like most informants, Gentile didn’t get a deal in writing, but he says the prosecutor promised to consider dropping the charges if he cooperated in good faith.

Shortly after being released from jail, Gentile called Gottbetter to arrange a meeting. They decided on breakfast at the members-only Core Club in Manhattan. Gentile arrived with a recording device in the pocket of his jacket, but Gottbetter was careful about what he said and didn’t want to discuss the gas deal. Instead he was eager to get Gentile’s help with a new scheme.

The meeting was an adrenaline rush for Gentile. His FBI handlers seemed excited, too. They agreed to pursue Gottbetter’s plan, and at the same time Gentile offered to go after other crooks, to improve the odds he’d be let off the hook. He began strategizing with the lead agent, Kevin Bradley, a tall man with prematurely white hair—the source of his nickname, A.C., for Anderson Cooper. Gentile says the two of them spoke nearly every day on the phone and met regularly at Palisades Center, a mall in West Nyack, N.Y. Gentile’s handlers would identify suspicious traders and encourage him to set up meetings. He told them he’d need higher-tech gadgets to avoid detection, so they gave him a set of keys with a hidden recorder and realistic-looking Starbucks gift cards that recorded audio. He sometimes wore a white dress shirt with a button that concealed a tiny camera.

At first, Gentile had a habit of coming on too strong. Among his early targets was a broker I know. He burst out laughing when I told him Gentile was an informant. They’d met at a bar, he recalled, where Gentile spoke so openly about pump-and-dump schemes that the broker asked if he was a cop and walked out. “The Oscar definitely did not go to him,” the broker said.

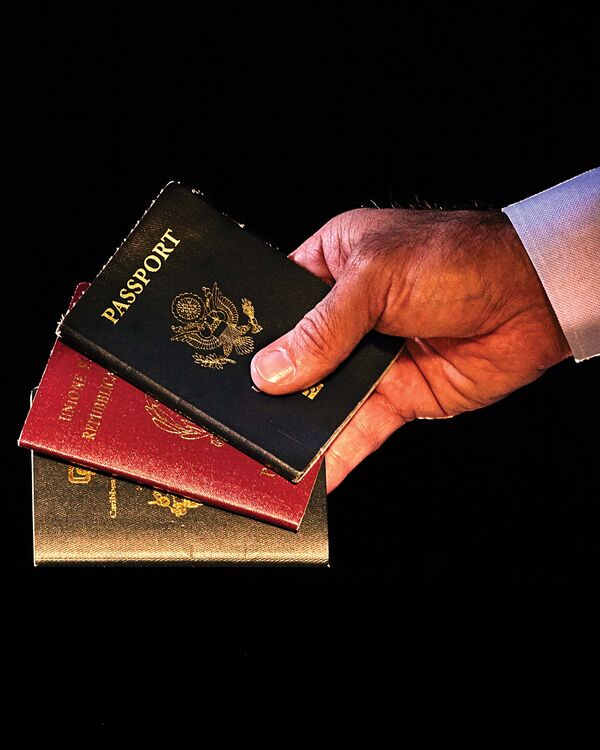

Gentile held passports for the U.S., the European Union, and Jamaica, which enriched his cover.

Photographer: Jeff Brown for Bloomberg Businessweek

But Gentile improved. He learned to play hard to get, waiting days to return calls and letting his targets do most of the talking. He developed a lure, telling them he’d created a trading algorithm that could swap shares back and forth among 32 accounts, at ever-higher prices, making it look like the stock was going up. The best part, he’d say, was that it was completely untraceable because he would run it through his offshore brokerage. Crooks loved the idea. “I was really just selling bullshit,” Gentile says. “I’d lie to them. I was a very good liar.” Sometimes he brought along an undercover FBI agent who pretended to be a financier; the aim was partly to ensure that, in the event of an arrest, someone other than Gentile could provide eyewitness testimony.

Most informants find the work scary. “Prison was a cakewalk compared to wearing a wire,” says Mark Whitacre, the Archer Daniels Midland Co. executive who became the subject of the book The Informant after helping expose an animal-feed additive price-fixing conspiracy. “I was almost delusional from the stress.” Not Gentile. Working undercover made him feel like an action hero. It fed into his love of intrigue, according to his ex-wife, Karen Barker-Gentile. “He did actually assume a new personality in which he imagined himself to be an FBI agent,” she says. He began calling his operation Wall Street Underground and developed a signature move, giving each target a hug at their last meeting before the FBI moved in.

The FBI agents encouraged this grandiosity, according to Gentile. He says they let him keep his Glock pistol; that Bradley, an avid cyclist, gave him the code name “Bianchi,” for the Italian racing bicycle; and that his handlers told him he was the best informant they’d ever worked with, more like an undercover agent than a cooperating witness. Gentile also kept running his Caribbean brokerage, traveling to and from the Bahamas.

As for Gottbetter, Gentile was gaining his trust. In August 2013, Gottbetter requested that they meet in the lounge at the White Plains airport. He flew in to tell Gentile about a deal centered on a shell company he and some other financiers controlled. Their plan was to use the company, which filings said grew mushrooms in El Salvador, to buy a bunch of cheap oil wells. Then they’d rename the company and hype it to investors.

The FBI’s problem was that nothing Gottbetter was describing was necessarily illegal. For the scheme to cross the line into fraud, Gentile would have to persuade Gottbetter to use his fake trading algorithm. “The government instructed me to criminalize the deal,” Gentile says. “I felt like I was tricking him.” (The FBI declined to comment on Gentile’s allegation and other facets of his account.)

Three months later, on a cold November night, Bradley and other FBI agents waited outside the Surrey, a hotel on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, where Gentile’s final meeting with Gottbetter was taking place. Gottbetter had with him a British man who was supposed to finance the company’s oil well investments. They spent hours talking over the plan, finally agreeing that Gentile would use his untraceable accounts to make it appear as though the stock price was going up. Gentile surreptitiously snapped a picture of the investor and sent it to the agents so they’d know whom to arrest.

As they said goodbye in the lobby, Gentile pulled the investor in for a hug and kissed him on the cheek. Gentile and Gottbetter left, and the agents went into the building and nabbed the investor. They later told Gentile that he’d gotten them the evidence they needed on Gottbetter, who eventually admitted to securities fraud, paid $5 million in fines, and served about a year in prison and a halfway house. (Through his lawyer, Gottbetter declined to comment for this article, “other than to say that he has taken responsibility for his conduct, which was aberrational.”)

The FBI’s primary target was out of commission, but Gentile was still on the hook: The bureau wanted him to continue informing on others. He began to wonder when he’d be able to stop and whether the agents were making empty promises. And he worried about how, if they reneged on the deal, he would prove he’d been a cooperator. Gentile decided to get proof of their arrangement by surreptitiously recording his handlers. “They taught me tapes don’t lie,” he says.

In February 2014, Bradley and his FBI boss told Gentile that internal investigators were auditing their spending on his operations. In two years they’d spent a few hundred thousand dollars on expenses, Gentile says, including about $15,000 for his travel. The agents told him that an investigator would be asking him some questions, and they wanted to go over what to say. They called a meeting at the Red Robin restaurant at Palisades Center. This time, Gentile brought a recording device of his own.

At the meeting, Bradley, his boss, and other agents praised Gentile’s work. Bradley said he’d fulfilled his agreement with the prosecutor. “Look at how you affected this space. How many people you shut down,” Bradley’s boss said, while the tape (which I later heard) rolled. “We never would have gotten near those people without you.” Gentile told the agents he wanted to work for the agency as a consultant one day, and they didn’t shoot the idea down.

A still from surveillance footage of Gentile (top), Bradley (bottom), and another FBI agent conferring in the Bahamas about the Milrud investigation.

The agents went through the questions Gentile might be asked by the internal investigator, telling him not to say much. They advised him to say he hadn’t directed any criminal activity. (“Of course I did,” Gentile says.) And they said not to mention his gun.

When the investigator called, Gentile stuck to the script. He still doesn’t know whether anything came of the inquiry. More important to him was that he had the agents on tape saying he’d held up his end of the deal. He also had what he thought was evidence of them acting unethically. Over the next year he recorded more than 100 other calls.

During that period, the agents were letting Gentile suggest his own targets. One was Nonko Trading, a rival brokerage; Gentile taped one of its employees admitting the firm had defrauded investors, and prosecutors arrested the owner. Another was a high-frequency trader named Alex Milrud. Gentile suggested the sting because, he says, Milrud once cheated him out of $70,000. Gentile lured Milrud to the Bahamas and persuaded him to show how he used puppet accounts in China to manipulate stocks. After Milrud was charged, in January 2015, the FBI issued a statement describing the alleged crime as “a sophisticated, international, groundbreaking market manipulation scheme.” Milrud pleaded guilty and is awaiting sentencing; through his lawyer, he denied ripping off Gentile and otherwise declined to comment.

By early 2015, Gentile was running out of targets. That June, his worst fear came true: Prosecutors told him he’d have to plead guilty to a felony stemming from the original charges against him. They said he wouldn’t serve any time in prison, but Gentile nevertheless felt betrayed. He’d delivered more than he promised, and he wanted the charges to disappear. “I kept saying no,” he says. “Sorry, that wasn’t the deal, we aren’t taking it.” Then he played what he thought was his trump card: “By the way, we also have these tapes.”

Instead of forcing the prosecutors to let him go, the threat appeared to anger them. The following spring, they rearrested him and charged him for his alleged participation in the original gold mine and natural gas pump-and-dump schemes. The charges carried a maximum prison term of 20 years, but Gentile doesn’t regret rejecting the government’s no-jail-time offer. “Only someone who’s crazy wouldn’t take the deal,” he says, “unless he lives his life by principles and integrity.”

Gentile was allowed to remain free on $500,000 bail. He told his friends he would beat the case and met up with a rapper he’d signed to his old Miami reggae label, to make a song about snitching. On the track, Gentile raps awkwardly over a wobbly beat from a drum machine: “The feds don’t know who they got, bro/ I’m going rogue.” He says he dated a Puerto Rican beauty pageant winner and a “hotter girl from Spanish class.” He binge-watched Billions, the Showtime series about a prosecutor out to get a hedge fund manager at all costs. “It’s like the story of my life,” he says.

For his 40th birthday last year, he threw a James Bond-themed party for 80 guests at a rented beach house in the Bahamas. Brent Mayson, one of his best friends, recalls that Gentile jumped onto a giant inflatable swan in the pool wearing a borrowed Armani jacket. “It’s spring break for him every day,” says Mayson, a real estate developer. “I think it’s kind of adorable. He’s living out his youth a little later.”

Gentile obsessed over old rulings that he was convinced illustrated flaws in the case against him. His lawyers filed a motion to dismiss the case, detailing Gentile’s time undercover and claiming he’d been promised he wouldn’t be charged if he was successful. In response, prosecutors acknowledged that Gentile had provided useful information, but they said no one had promised him he’d get off scot-free and that the charges were merited. “What made Gentile such an accomplished criminal explains why he was such a valuable cooperator—he was deeply enmeshed in the world of stock market manipulation,” the prosecutors wrote.

Gentile blames the prosecutors, not Bradley or his other handlers, for bringing the case against him. In December, Bradley came to the courtroom to watch a hearing in Gentile’s case. During a break, he told Gentile that the other agents sent their regards, and they spoke about getting a beer together once the case was resolved. Bradley wouldn’t discuss the allegations about the internal investigation, nor specific facets of Gentile’s story. “Some of it is fairy tale-ish,” he says, “but he’s got a decent head on his shoulders.”

A month after the hearing, Gentile was driving home from the gym when one of his lawyers called. The judge had tossed out the charges, saying the statute of limitations had expired. Gentile was so relieved he started crying. Then he posted a Wolf of Wall Street meme on Instagram with the caption “F--- YOU ALL.” A spokesman for the U.S. attorney in New Jersey declined to say whether the office will appeal the ruling or otherwise comment on the case. Gentile still faces a related civil lawsuit filed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, seeking his share of $17 million in proceeds from the alleged schemes. He says he believes he’ll prevail on the same statute-of-limitations grounds.

Gentile says he feels sorry for the people he informed on, and that some of them wouldn’t have committed crimes if he hadn’t talked them into it. But even if his targets wouldn’t have done something outright criminal, they were planning to cash in by hyping dubious stocks. Schemes like these cost investors billions of dollars every year. Gentile’s methods weren’t pretty, but without them, Gottbetter and the others would still be free to siphon people’s savings.

Gentile isn’t ready to give up the hustle. He says he intends to sue the government for damages and that one day he’d like to star in the movie of his life. His time undercover, he says, gave him the acting skills he needs. And the storyline will be straight off the posters on his office walls. “I’m going to build a billion-dollar company,” he says. “I’m going to get my own private jet, I’m going to drive a flashy car. And I’m going to make my license plate F---YOUDOJ.”

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento