Heydar Aliyev Prospekti, a broad avenue in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, connects the airport to the city. The road is meant to highlight Baku’s recent modernization, and it is lined with sleek new buildings. The Heydar Aliyev Center, an undulating wave of concrete and glass, was designed by Zaha Hadid. The state oil company is housed in a twisting glass tower, and the headquarters of the state water company looks like a giant water droplet. “It’s like Potemkin,” my translator told me. “It’s only the buildings right next to the road.” Behind the gleaming structures stand decaying Soviet-era apartment blocks, with clothes hanging out of windows and wallboards exposed by fallen brickwork.

As you approach the city center, a tower at the end of the avenue looms in front of you. Thirty-three stories high and curved to resemble a sail, the building was clearly inspired by the Burj Al Arab Hotel, in Dubai, but it is boxier and less elegant. When I visited Baku, in December, five enormous white letters glowed at the top of the tower: T-R-U-M-P.

The building, a five-star hotel and residence called the Trump International Hotel & Tower Baku, has never opened, though from the road it looks ready to welcome the public. Reaching the property is surprisingly difficult; the tower stands amid a welter of on-ramps, off-ramps, and overpasses. During the nine days I was in town, I went to the site half a dozen times, and on each occasion I had a comical exchange with a taxi-driver who had no idea which combination of turns would lead to the building’s entrance.

The more time I spent in the neighborhood, the more I wondered how the hotel could have been imagined as a viable business. The development was conceived, in 2008, as a high-end apartment building. In 2012, after Donald Trump’s company, the Trump Organization, signed multiple contracts with the Azerbaijani developers behind the project, plans were made to transform the tower into an “ultra-luxury property.” According to a Trump Organization press release, a hotel with “expansive guest rooms” would occupy the first thirteen floors; higher stories would feature residences with “spectacular views of the city and Caspian Sea.” For an expensive hotel, the Trump Tower Baku is in an oddly unglamorous location: the underdeveloped eastern end of downtown, which is dominated by train tracks and is miles from the main business district, on the west side of the city. Across the street from the hotel is a discount shopping center; the area is filled with narrow, dingy shops and hookah bars. Other hotels nearby are low-budget options: at the AYF Palace, most rooms are forty-two dollars a night. There are no upscale restaurants or shops. Any guests of the Trump Tower Baku would likely feel marooned.

The timing of the project was also curious. By 2014, when the Trump Organization publicly announced that it was helping to turn the tower into a hotel, a construction boom in Baku had ended, and the occupancy rate for luxury hotels in the city hovered around thirty-five per cent. Jan deRoos, of Cornell University, who is an expert in hotel finance, told me that the developer of a five-star hotel typically must demonstrate that the project will maintain an average occupancy rate of at least sixty per cent for ten years. There is a long-term master plan to develop the area around the Trump Tower Baku, but if it is implemented the hotel will be surrounded for years by noisy construction projects, making it even less appealing to travellers desiring a luxurious experience—especially considering that there are many established hotels on the city’s seaside promenade. There, an executive from ExxonMobil or the Israeli cell-phone industry can stay at the Four Seasons, which occupies a limestone building that evokes a French colonial palace, or at the J. W. Marriott Abershon Baku, which has an outdoor terrace overlooking the water. Tiffany, Ralph Lauren, and Armani are among the dozens of companies that have boutiques along the promenade.

A former top official in Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Tourism says that, when he learned of the Trump hotel project, he asked himself, “Why would someone put a luxury hotel there? Nobody who can afford to stay there would want to be in that neighborhood.”

The Azerbaijanis behind the project were close relatives of Ziya Mammadov, the Transportation Minister and one of the country’s wealthiest and most powerful oligarchs. According to the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index, Azerbaijan is among the most corrupt nations in the world. Its President, Ilham Aliyev, the son of the former President Heydar Aliyev, recently appointed his wife to be Vice-President. Ziya Mammadov became the Transportation Minister in 2002, around the time that the regime began receiving enormous profits from government-owned oil reserves in the Caspian Sea. At the time of the hotel deal, Mammadov, a career government official, had a salary of about twelve thousand dollars, but he was a billionaire.

The Trump Tower Baku originally had a construction budget of a hundred and ninety-five million dollars, but it went through multiple revisions, and the cost ended up being much higher. The tower was designed by a local architect, and in its original incarnation it had an ungainly roof that suggested the spikes of a crown. A London-based architecture firm, Mixity, redesigned the building, softening its edges and eliminating the ornamental roof. By the time the Trump team officially joined the project, in May, 2012, many condominium residences had already been completed; at the insistence of Trump Organization staffers, most of the building’s interior was gutted and rebuilt, and several elevators were added.

After Donald Trump became a candidate for President, in 2015, Mother Jones, the Associated Press, the Washington Post, and other publications ran articles that raised questions about his involvement in the Baku project. These reports cited a series of cables sent from the U.S. Embassy in Azerbaijan in 2009 and 2010, which were made public by WikiLeaks. In one of the cables, a U.S. diplomat described Ziya Mammadov as “notoriously corrupt even for Azerbaijan.” The Trump Organization’s chief legal officer, Alan Garten, told reporters that the Baku hotel project raised no ethical issues for Donald Trump, because his company had never engaged directly with Mammadov.

Cartoon

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

According to Garten, Trump played a passive role in the development of the property: he was “merely a licensor” who allowed his famous name to be used by a company headed by Ziya Mammadov’s son, Anar, a young entrepreneur. It’s not clear how much money Trump made from the licensing agreement, although in his limited public filings he has reported receiving $2.8 million. (The Trump Organization shared documents that showed an additional payment of two and a half million dollars, in 2012, but declined to disclose any other payments.) Trump also had signed a contract to manage the hotel once it opened, for an undisclosed fee tied to the hotel’s performance. The Washington Post published Garten’s description of the deal, and reported that Donald Trump had “invested virtually no money in the project while selling the rights to use his name and holding the contract to manage the property.”

A month after Trump was elected President, Garten announced that the Trump Organization had severed its ties with the hotel project, describing the decision to CNN as little more than “housecleaning.” I was in Baku at the time, and it had become clear that the Trump Organization’s story of the hotel was incomplete and inaccurate. Trump’s company had made the deal not just with Anar Mammadov but also with Ziya’s brother Elton—an influential member of the Azerbaijani parliament. Elton signed the contracts, and in an interview he confirmed that he founded Baku XXI Century, the company that owns the Trump Tower Baku. When he was asked who owns Baku XXI Century, he called it a “commercial secret” but added that he “controlled all its operations” until 2015, when he cut ties to the company. Elton denied having used his political position for profit.

An Azerbaijani lawyer who worked on the project revealed to me that the Trump Organization had not just licensed the family name; it also had signed a technical-services agreement in which it promised to help its partner meet Trump design standards. Technical-services agreements are often nominal addenda to licensing deals. Major hospitality brands compile exhaustive specifications for licensed hotels, and tend to approve design elements remotely; a foreign site is visited only occasionally. But in the case of Trump Tower Baku the oversight appears to have been extensive. The Azerbaijani lawyer told me, “We were always following their instructions. We were in constant contact with the Trump Organization. They approved the smallest details.” He said that Trump staff visited Baku at least monthly to give the go-ahead for the next round of work orders. Trump designers went to Turkey to vet the furniture and fabrics acquired there. The hotel’s main designer, Pierre Baillargeon, and several contractors told me that they had visited the Trump Organization headquarters, in New York, to secure approval for their plans.

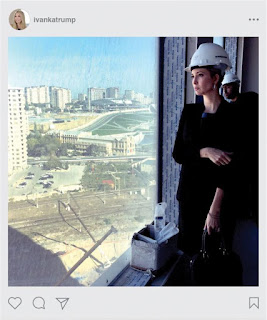

Ivanka Trump was the most senior Trump Organization official on the Baku project. In October, 2014, she visited the city to tour the site and offer advice. An executive at Mace, the London-based construction firm that oversaw the tower’s conversion to a hotel, met with Ivanka in Baku and New York. He told me, “She had very strong feelings, not just about the design but about the back of the hotel—landscaping, everything.” The Azerbaijani lawyer said, “Ivanka personally approved everything.” A subcontractor noted that Ivanka’s team was particular about wood panelling: it chose an expensive Macassar ebony, from Indonesia, for the ceiling of the lobby. The ballroom doors were to be made of book-matched panels of walnut. On her Web site, Ivanka posted a photograph of herself wearing a hard hat inside the half-completed hotel. A caption reads, “Ivanka has overseen the development of Trump International Hotel & Tower Baku since its inception, and she recently returned from a trip to the fascinating city in Azerbaijan to check in on the project’s progress.” (Ivanka Trump declined requests to discuss the Baku project.)

Jan deRoos, the Cornell professor, developed branded-hotel properties before entering academia. He told me that the degree of the Trump Organization’s involvement in the Baku property was atypical. “That’s very, very intense,” he said.

The sustained back-and-forth between the Trump Organization and the Mammadovs has legal significance. If parties involved in the Trump Tower Baku project participated in any illegal financial conduct, and if the Trump Organization exerted a degree of control over the project, the company could be vulnerable to criminal prosecution. Tom Fox, a Houston lawyer who specializes in anti-corruption compliance, said, “It’s a problem if you’re making a profit off of someone else’s corrupt conduct.” Moreover, recent case law has established that licensors take on a greater legal burden when they assume roles normally reserved for developers. The Trump Organization’s unusually deep engagement with Baku XXI Century suggests that it had the opportunity and the responsibility to monitor it for corruption.

Before signing a deal with a foreign partner, American companies, including major hotel chains, conduct risk assessments and background checks that take a close look at the country, the prospective partner, and the people involved. Countless accounting and law firms perform this service, as do many specialized investigation companies; a baseline report normally costs between ten thousand and twenty-five thousand dollars. A senior executive at one of the largest American hotel chains, who asked for anonymity because he feared reprisal from the Trump Administration, said, “We wouldn’t look at due diligence as a burden. There certainly is a cost to doing it, especially in higher-risk places. But it’s as much an investment in the protection of that brand. It’s money well spent.”

Alan Garten told me that the Trump Organization had commissioned a risk assessment for the Baku deal, but declined to name the company that had performed it. The Washington Post article on the Baku project reported that, according to Garten, the Trump Organization had undertaken “extensive due diligence” before making the hotel deal and had not discovered “any red flags.”

But the Mammadov family, in addition to its reputation for corruption, has a troubling connection that any proper risk assessment should have unearthed: for years, it has been financially entangled with an Iranian family tied to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, the ideologically driven military force. In 2008, the year that the tower was announced, Ziya Mammadov, in his role as Transportation Minister, awarded a series of multimillion-dollar contracts to Azarpassillo, an Iranian construction company. Keyumars Darvishi, its chairman, fought in the Iran-Iraq War. After the war, he became the head of Raman, an Iranian construction firm that is controlled by the Revolutionary Guard. The U.S. government has regularly accused the Guard of criminal activity, including drug trafficking, sponsoring terrorism abroad, and money laundering. Reuters recently reported that the Trump Administration was poised to officially condemn the Revolutionary Guard as a terrorist organization.

I asked Garten how deeply the Trump Organization had looked into the Mammadov family’s political connections. Had it been concerned that Elton Mammadov, as a sitting member of parliament, might exploit his power to benefit the project? How much money had Ziya Mammadov invested in Elton’s company? Garten noted that he didn’t oversee the due-diligence process. “The people who did are no longer at the company,” he said. “I can’t tell you what was done in this situation.” He would not identify the former employees. When I asked him to provide documentation of due diligence, he said that he couldn’t share it with me, because “it’s confidential and privileged.”

A 2014 Instagram post of Ivanka Trump at the Baku tower.

A 2014 Instagram post of Ivanka Trump at the Baku tower.

Photo Illustration by The New Yorker

No evidence has surfaced showing that Donald Trump, or any of his employees involved in the Baku deal, actively participated in bribery, money laundering, or other illegal behavior. But the Trump Organization may have broken the law in its work with the Mammadov family. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, passed in 1977, forbade American companies from participating in a scheme to reward a foreign government official in exchange for material benefit or preferential treatment. The law even made it a crime for an American company to unknowingly benefit from a partner’s corruption if it could have discovered illicit activity but avoided doing so. This closed what was known as the “head in the sand” loophole.

As a result, American companies must examine potential foreign partners very carefully before making deals with them. I recently spoke with Alexandra Wrage, who runs Trace International, a consortium of three hundred corporations that do business overseas. Trace helps these firms avoid violating the F.C.P.A., and it has a division that can be hired by individual clients to assess potential foreign partners. To comply with the law, Wrage noted, an American company must remain vigilant even after a contract is signed, monitoring its foreign partner to be sure that nobody involved is engaging in bribery or other improprieties.

Wrage pointed out that corrupt government leaders often use their children or their siblings to distance themselves from illicit projects. Such an official creates a company in the relative’s name which appears to be independent but is controlled by the official. To lessen the likelihood of an F.C.P.A. violation when working with a company that is owned by a child or a sibling of a government minister, Wrage told me, “you’d need to show that the child has real expertise, real ability to do the work.” Otherwise, Wrage said, “the assumption is that they are a partner entirely because of their ability to use their parent’s power.” Before Elton Mammadov became a member of parliament, in 2000, he was a maintenance engineer who had no experience in real-estate development. When the Trump Organization joined the Baku project, it barred a Mammadov-owned company from doing construction work, because it was deemed incompetent.

Wrage said that a U.S. company looking to make a deal with a foreign partner should be confident that the partner has a reasonable likelihood of making a profit from the venture. If the project seems almost guaranteed to lose money, it could well be a bribery scheme or some other criminal operation. The partner also should uphold modern accounting standards.

“It’s simple,” she said. “Will money flow through this business because it offers a compelling product at a decent price, or will the money come because of an illicit relationship with someone who uses their power?”

Wrage told me that, in 2009, an American entrepreneur was successfully prosecuted for his part in a corruption conspiracy in Azerbaijan. Frederic Bourke, the co-founder of Dooney & Bourke, the handbag company, had invested in a project in which a foreign partner paid bribes to Azerbaijani government officials and their family members. Bourke was sentenced to a year in prison for violating the F.C.P.A.; he appealed the conviction, claiming ignorance of the corruption. Two years later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the conviction, saying that, regardless of whether he had known about the bribes, “the testimony at trial demonstrated that Bourke was aware of how pervasive corruption was in Azerbaijan.” The F.C.P.A., they said, also criminalized “conscious avoidance”—a deliberate effort to remain in the dark about any transgressions a foreign partner might be involved in. After Bourke’s conviction, Wrage said, U.S. companies were well aware of the dangers of making careless deals in Azerbaijan.

Even a cursory look at the Mammadovs suggests that they are not ideal partners for an American business. Four years before the Trump Organization announced the Baku deal, WikiLeaks released the U.S. diplomatic cables indicating that the family was corrupt; one cable mentioned the Mammadovs’ link to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. In 2013, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project investigated the Mammadov family’s corruption and published well-documented exposés. Six months before the hotel announcement, Foreign Policy ran an article titled “The Corleones of the Caspian,” which suggested that the Mammadovs had exploited Ziya’s position as Transportation Minister to make their fortunes.

The Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty investigation revealed that Baku XXI Century, the company controlled by Elton, had at least two other stakeholders. One of them was a company called zqan, an acronym for the family members of the Transportation Minister: Ziya Mammadov; Qanira, his wife; Anar, his son; and Nigar, his daughter. Anar is the official head of zqan. Another stakeholder in Baku XXI Century was the Baghlan Group, a company run by an Azerbaijani businessman who is known to be close to Ziya Mammadov.

Baku XXI Century, zqan, and Baghlan have so many overlapping interests that they often seem to operate as a single concern. According to the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty investigation, the companies all prospered largely through contracts with the Transportation Ministry. The Trump Tower Baku complex was built partly on land controlled by the ministry. A Baghlan subsidiary received a contract from the ministry to import a thousand London-style cabs to Baku. Soon afterward, ministry inspectors began preventing competing taxi services from parking in the city center or at subway stops. Another new rule required all taxi owners to pay taxes and license fees at the Bank of Azerbaijan, a private entity that at the time was owned jointly by Anar Mammadov and Baghlan.

Anar’s net worth has been estimated at a billion dollars, but he is not a self-made man. According to the Associated Press, zqan was founded in 2000, when he was in his late teens. He began studying in England that year, and remained there until 2005; during that period, the company that he ostensibly ran experienced explosive growth. Trump Organization officials, as well as others familiar with the Baku project, told me that during the tower’s construction Anar was barely involved, and was often travelling abroad. (He flies on a Gulfstream G450 private jet.) An American who did business in Azerbaijan told me, “It’s common knowledge there that Ziya Mammadov controls zqan.”

One of the cables sent in 2010 by the U.S. Embassy in Baku noted that, “with so much of the nation’s oil wealth being poured into road construction,” the Mammadovs had become disproportionately powerful in Azerbaijan. Another cable suggested that Ziya controlled zqan, the country’s “largest commercial development company.” This cable described Ziya as being the object of “many allegations from Azerbaijani contacts of creative corrupt practices.”

Much of the land occupied by the Trump Tower Baku complex was once packed with houses. In 2011, residents received letters from the local government authority informing them that their homes were to be demolished to make way for a project of crucial government significance. Thirty families were evicted. One resident, Minaye Azizova, told me that the government gave her eighteen thousand dollars in compensation for a home that, by her estimation, was worth five times as much. After she discovered that her home had been condemned so that Baku XXI Century could build a luxury tower, she sued the government.

Cartoon

“Turns out the sound of the squeaky toy was coming from inside the house.”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

Construction of the building began in 2008. I have spoken with more than a dozen contractors who worked on it. Some of them described behavior that seemed nakedly corrupt. Frank McDonald, an Englishman who has had a long career doing construction jobs in developing countries, performed extensive work on the building’s interior. He told me that his firm was always paid in cash, and that he witnessed other contractors being paid in the same way. At the offices of Anar Mammadov’s company, he said, “they would give us a giant pile of cash,” adding, “I got a hundred and eighty thousand dollars one time, which I fit into my laptop bag, and two hundred thousand dollars another time.” Once, a colleague of his picked up a payment of two million dollars. “He needed to bring a big duffelbag,” McDonald recalled. The Azerbaijani lawyer confirmed that some contractors on the Baku tower were paid in cash.

Two people who worked on the Trump Tower Baku told me that bribes were paid. Much of the graft was routine: Azerbaijani tax officials, government inspectors, and customs officers showed up occasionally to pick up envelopes of cash.

The executive at Mace, the construction firm, told me that the Mammadovs handled payments and all interactions with the Azerbaijani government. “Were people bribed?” he said. “I don’t know. Maybe. We didn’t check.” (A spokesman for Mace said that the firm was “not involved” in any corruption.)

Pierre Baillargeon, the architect whom the Mammadovs hired to alter the tower’s original design, is a Canadian who runs a studio in London. He has often worked in parts of the world known for corruption, including Sudan and Syria, and has done several projects in Azerbaijan. In a phone interview, Baillargeon said that he knew nothing about corruption and was “just a designer.” I asked him why he thought the hotel had been built in such an inhospitable part of Baku. “Every project has detractors,” he said. When I asked him if he had seen large payments being made in cash, he hung up. (He did not respond to later calls.)

Alan Garten, the Trump Organization lawyer, did not deny that there was corruption involved in the project. “I’m not going to sit here and defend the Mammadovs,” he said. But, from a legal standpoint, he argued, the Trump Organization was blameless. In his opinion, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act doesn’t apply to the Baku deal, even if corruption occurred. “We didn’t own it,” he said of the hotel. “We had no equity. We didn’t control the project. The flow of funds is in the wrong direction.” He added, “We did not pay any money to anyone. Therefore, it could not be a violation of the F.C.P.A.”

“No, that’s just wrong,” Jessica Tillipman, an assistant dean at George Washington University Law School, who specializes in the F.C.P.A., said. “You can’t go into business deals in Azerbaijan assuming that you are immune from the F.C.P.A.” She added, “Nor can you escape liability by looking the other way. The entire Baku deal is a giant red flag—the direct involvement of foreign government officials and their relatives in Azerbaijan with ties to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. Corruption warning signs are rarely more obvious.”

Tillipman explained that the F.C.P.A. defines corruption as “the payment of money or anything of value” to a foreign official. Last year, JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay two hundred and sixty-four million dollars to settle charges that it had violated the F.C.P.A.; the bank had given jobs and internships to relatives and friends of government officials in Asia. Tillipman, along with several other F.C.P.A. experts, told me that the Trump Organization had clearly provided things of value in the Baku deal: its famous brand, its command of the luxury market, its extensive technical advice.

In May, 2012, the month the Baku deal was finalized, the F.C.P.A. was evidently on Donald Trump’s mind. In a phone-in appearance on CNBC, he expressed frustration with the law. “Every other country goes into these places and they do what they have to do,” he said. “It’s a horrible law and it should be changed.” If American companies refused to give bribes, he said, “you’ll do business nowhere.” He continued, “There is one answer—go to your room, close the door, go to sleep, and don’t do any deals, because that’s the only way. The only way you’re going to do it is the other way.”

It is unclear how the Trump Administration plans to approach F.C.P.A. enforcement. Jay Clayton, Trump’s choice to run the Securities and Exchange Commission, co-authored a paper in 2011 arguing that American companies were at a severe disadvantage because of the U.S. government’s “singular strategy of zealous enforcement.” But Jeff Sessions, the new Attorney General, told the Senate Judiciary Committee during his confirmation hearings that he will continue to uphold the F.C.P.A.

After 9/11, prosecuting financial corruption acquired new political importance. The C.I.A. and other intelligence services came to believe that preventing illicit money from flowing through the global financial system was a necessary tactic in preventing future terrorist attacks, and the U.S. led an international effort to enforce financial transparency. Banks and other financial entities were required to vet their clients aggressively and to report any suspicious activity. Prosecutions for money laundering, bribery, and other financial crimes rose significantly. In 2000, the government launched three prosecutions under the F.C.P.A. Last year, it initiated fifty-four.

Investigators of financial fraud like to say that government corruption, money laundering, and other illicit behavior often form a “nexus” with even more troubling activity, such as financing terrorism and developing weapons of mass destruction. This appears to be true in the Baku deal. As the Mammadovs were preparing to build the tower, the family patriarch, Ziya, was cementing his financial relationship with the Darvishis, the Iranian family with ties to the country’s Revolutionary Guard.

At least three Darvishis—the brothers Habil, Kamal, and Keyumars—appear to be associates of the Guard. In Farsi press accounts, Habil, who runs the Tehran Metro Company, is referred to as a sardar, a term for a senior officer in the Revolutionary Guard. A cable sent on March 6, 2009, from the U.S. Embassy in Baku described Kamal as having formerly run “an alleged Revolutionary Guard-controlled business in Iran.” The company, called Nasr, developed and acquired instruments, guidance systems, and specialty metals needed to build ballistic missiles. In 2007, Nasr was sanctioned by the U.S. for its role in Iran’s effort to develop nuclear missiles.

The cable said that Kamal and Keyumars were frequent visitors to Azerbaijan; Kamal had recently established “a close business relationship/friendship” with Ziya Mammadov, and, with Mammadov’s assistance, had been awarded “at least eight major road construction and rehabilitation contracts, including contracts for construction of the Baku-Iranian Astara highway.” (Keyumars also seems to have been involved in these deals.) The cable added, “We assume Mammedov [sic] is a silent partner in these contracts.”

Cartoon

“Does the No. 1 stop here and does that go to Penn Station and can I get a train there to Philadelphia and then how do I get to Walnut Street?”

JANUARY 10, 2011

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

Iran has two militaries. The Iranian Army is a conventional force whose mission is to protect the country. The Revolutionary Guard is an independent force of about a hundred and fifty thousand soldiers, whose duty is to protect the country’s Islamic system and to preserve the power of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The Revolutionary Guard has its own air force and navy, and it has a unit known as the Quds Force, which the United States has identified as a major supporter of Hezbollah and other international terrorist groups. The Guard has developed a shadow economy within Iran to fund its activities and expand its power. It controls all official border crossings and runs several unofficial ports, solely for its own use. The Revolutionary Guard smuggles into the country everything from consumer goods blocked by sanctions to drugs. It also owns seemingly legitimate companies in construction, energy, telecommunications, auto manufacturing, and banking. According to the United States Institute of Peace, the Guard is linked “to dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of companies that appear to be private in nature but are run by [Revolutionary Guard] veterans.”

J. Matthew McInnis, an Iran expert at the American Enterprise Institute, who served as a consultant to Michael Flynn when Flynn was the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, told me that owners of Revolutionary Guard-related businesses often become rich. But there is a catch: from time to time, they should expect to be asked to serve the needs of the Guard. “When the Revolutionary Guard says, ‘We need to move some illicit stuff,’ or ‘We need new parts for our missiles,’ they reach out to these guys,” McInnis explained. “It’s a soft network that can do all sorts of things that are very hard to trace.”

Keyumars Darvishi once ran Raman, a construction firm that is owned by the Islamic Revolution Mostazafan Foundation. According to the United Nations, the foundation is a major financial arm of the Revolutionary Guard. Keyumars left Raman to run Azarpassillo, the putatively independent construction company that received multiple road contracts in Azerbaijan. According to Azarpassillo’s Web site, it was incorporated in 2008. In recent years, Keyumars has also served as the acting director of the Tehran Metro Company, filling in for his brother Habil.

Mehrzad Boroujerdi, a political scientist at Syracuse University, who studies the political, economic, and military élite of Iran, said, “It looks like Azarpassillo is a front organization for the Revolutionary Guard.” He found it inconceivable that Keyumars Darvishi, after working for years in a company controlled by the Revolutionary Guard, would quit, raise large amounts of capital on his own, and then become the head of a fully independent company that competed against Revolutionary Guard fronts for contracts. Khatam Al-Anbia, an Iranian construction giant that is controlled by the Guard and is under U.S. sanctions, has subcontracted Azarpassillo on at least two major infrastructure projects in Iran. The Tehran Metro Company is also involved in both projects. McInnis told me, “If you see a connection with Khatam Al-Anbia, you would assume the connections to the Revolutionary Guard are there. The suspicion of Azarpassillo being a front company is certainly worth investigating. It would fit a normal pattern.”

Alan Garten told me that the Trump Organization checks to see if potential Trump partners are on “watch lists and sanctions lists,” and that the company knew nothing of Ziya Mammadov’s relationship to the Darvishis until 2015, when it learned that “certain principals associated with the developer may have had some association with some problematic entities.” And yet, by that point, the U.S. Embassy cables had been online for four years. Garten insisted that the Trump Organization still has no idea if the association between the Mammadovs and the Darvishis is real, or if it’s simply an allegation “spread by the media.” I recently spoke with Allison Melia, who until 2015 was one of the C.I.A.’s lead analysts of Iran’s economy; she now works for the Crumpton Group, a strategic advisory firm whose services include conducting due diligence for companies. She told me that her team could have compiled a dossier on the Mammadovs and their connection to the Revolutionary Guard in “a couple of days.” She said that any reputable investigative firm conducting a risk assessment would have advised a U.S. company to avoid a deal with a family connected to the Revolutionary Guard.

The U.S. has imposed various sanctions on Iran since the Islamic Revolution, in 1979. In recent years, U.S. and international efforts have focussed on isolating Iran from the global financial system, in order to prevent it from funding terrorist groups and contributing to worldwide instability. In 2015, the U.N., spurred by the Obama Administration, reached an agreement with Iran, and lifted some sanctions in return for a slowdown of the country’s nuclear program. However, according to the Congressional Research Service, many sanctions against Iran remain in effect, because of the country’s “support for terrorism, its human-rights abuses, its interference in specified countries in the region, and its missile and advanced-conventional-weapons programs.” In December, 2015, the U.S. House of Representatives imposed additional sanctions on the Revolutionary Guard and its associated businesses.

American companies must insure that they are not receiving funds that originated with any sanctioned entity. Ignorance is not a defense, especially if there is ample warning that a foreign partner could have a link to such an entity. Most firms, upon hearing of even a slight chance of Iranian involvement, conduct due diligence that is much more extensive than what is typical for F.C.P.A. compliance. Erich Ferrari, an attorney who specializes in sanctions-related legal cases, said that before the Trump Organization cashed any checks it should have been certain of “the source of the funds”—“not only the bank it was remitted from but how the Mammadovs actually earned the money they paid.” He said of the Baku deal, “It takes a lot to shock a lawyer, but I’ve had very few clients do so little due diligence.”

The nexus between the Mammadovs and the Darvishis suggests both opportunism and desperation. Ziya Mammadov is sixty-four, and in recent years the family’s position in Azerbaijan has begun to weaken. President Aliyev has systematically isolated, and then fired, longtime members of the regime in order to make way for his own cronies. From 2008 to 2014, Ziya Mammadov, perhaps fearing his ejection from political office, vastly increased his personal wealth.

During the same period, mounting international sanctions made it far more difficult for Iran to sell oil abroad, receive foreign funds, and import products. International banks became increasingly reluctant to accept funds from businesses owned by the Revolutionary Guard, severely limiting its ability to support allies such as Hezbollah and the Syrian government. At a moment when Iran was struggling to find ways to send money outside the country, Keyumars Darvishi joined Azarpassillo and began making one deal after another in Azerbaijan.

Ziya Mammadov apparently had complete discretion with regard to Azarpassillo’s projects. On April 6, 2007, Anne Derse, then the U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan, wrote in a cable that Charles Redman, at the time a senior vice-president for the American construction firm Bechtel, had recently met with Ziya Mammadov. Redman was looking for business, and knew that Azerbaijan was planning several major new roads. Bechtel could build them, he said, at an average cost of six million dollars per kilometre. Mammadov complained to him that this was too expensive. Bechtel ended up building nothing. Instead, much of the roadwork was done by Azarpassillo—at a much higher cost. According to a 2012 report by Azerbaijan’s Center for Economic and Social Development, an independent think tank, road construction during Mammadov’s tenure was “the most expensive in the world,” costing an average of eighteen million dollars per kilometre. (Derse declined to comment; Redman did not respond to e-mails.)

Cartoon

JULY 20, 2015

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

The available evidence strongly suggests that Ziya Mammadov conspired with an agent of the Revolutionary Guard to make overpriced deals that would enrich them both while allowing them to flout prohibitions against money laundering and to circumvent sanctions against Iran. Based on Ziya Mammadov’s past, it seems reasonable to assume that his main motive was profit. Like most Azerbaijanis, he is a secular Shiite Muslim, and he has no known ties to hard-line factions in Iran. Why did the Darvishis want to work with the Mammadovs? It might have caught their attention that the Mammadovs had their own private bank—one that had unfettered access to the global financial system.

While Azarpassillo was making deals with the Transportation Ministry, the Mammadovs were investing heavily in a series of large construction projects. Money launderers love construction projects. They attract legitimate funds from governments and private investors, and they require frequent payouts to legitimate subcontractors: cement factories, lumberyards, glass manufacturers, craftsmen. In the Trump Tower Baku project, money was going in and out of the U.S., the United Kingdom, Turkey, Romania, the United Arab Emirates, and several other countries. With such projects, it can be exceedingly difficult to detect the spread of illicit funds.

At the same time, the Mammadovs’ money was flowing through holding companies in offshore banking centers. According to leaked documents in the Panama Papers, companies controlled by the family have opened accounts in such places as the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, and Panama. The shell companies that list Mammadovs as beneficiaries or officers have bland names such as Trans-European Leasing Group and 1st Rate Investment, and many of them are owned by other shell companies.

In 2009, a year after Baku XXI Century began building the tower, the company opened the Baku International Bus Terminal, an enormous station that includes a shopping mall and a hotel. During this period, the Mammadov family also began building a hotel, a golf course, and a spa in the mountains north of Baku.

Meanwhile, the Mammadovs spent lavishly on themselves. Ziya built a mansion in one of the most expensive neighborhoods of Baku, and, on the beach, a villa whose walls are decorated to resemble ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs. Elton’s son, Aynar, became famous for having a collection of expensive cars, including a Ferrari, a Maserati, and a Lamborghini. Anar began using the Gulfstream G450, which typically costs forty-one million dollars, and bought a seven-bedroom home in London. He also spent millions of dollars on an effort to promote Azerbaijan in Washington, D.C., hosting galas for members of Congress and other powerful figures. A former associate of the Trump Organization told me that in 2012, on one of Anar’s trips to America, he visited Trump Tower, in New York, to meet with Donald Trump and company executives. (The Trump Organization would not confirm the visit.) Around this time, the contracts for the Baku project were issued.

Between 2004 and 2014, Mammadov family businesses spent more than half a billion dollars on large construction projects. They also poured money into a major construction-materials company, an insurance firm, and a new headquarters. It’s not clear how the Mammadovs funded such enormous investments while spending so much on themselves. They may have received loans, or secretly owned profitable businesses that supported the flurry of spending. Another explanation is that some of the investment money came from the Revolutionary Guard, through Azarpassillo.

Calls and e-mails to Azarpassillo, the Iranian Mission to the U.N., and the Azerbaijani government were not returned. Ziya and Anar Mammadov did not respond to requests for comment. Donald Trump has not addressed the Baku deal since becoming President. A Department of Justice spokesperson would not comment on the possibility of its investigating the Trump Tower Baku deal. The White House declined to comment.

If, as Alan Garten told me, the Trump Organization learned in 2015 about “the possibility” that the Mammadovs had ties to the Revolutionary Guard, it is striking that the company did not end the Baku deal until December, 2016. During this period, Garten told me, the Trump Organization never asked its Azerbaijani partners about the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, but it did send several default notices for late payments.

Throughout the Presidential campaign, Trump was in business with someone that his company knew was likely a partner with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. In a March, 2016, speech before the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, Trump said that his “No. 1 priority is to dismantle the disastrous deal with Iran.” Calling Iran the “biggest sponsor of terrorism around the world,” he promised, “We will work to dismantle that reach—believe me, believe me.” In the speech, Trump lamented that Iran had been allowed to develop new long-range ballistic missiles. According to Iran Watch, an organization that monitors Iran’s military capabilities, much of the technology to make the missiles was provided by Nasr, the company once run by Kamal Darvishi.

I asked Garten why the Trump Organization hadn’t cancelled the Baku contract in 2015. He said that there was “no rush,” because “the project had already stalled and was showing no signs of moving forward.” The Azerbaijani lawyer who worked on the project has seen the hotel’s interior, and told me that it is almost finished. In an interview with the magazine Baku, published in April, 2015, Ivanka Trump said that she was eager to enjoy the hotel’s “huge spa area,” and promised that the hotel would open “in June.”

Moreover, Garten said, the Trump Organization had signed binding contracts with the Mammadovs and couldn’t simply abandon its agreements. But Jessica Tillipman, the law-school assistant dean, told me, “You can’t violate sanctions just because you have a contract with someone.” According to Erich Ferrari, the lawyer who specializes in sanctions, companies that learn of a possible sanctions violation typically commission a “look-back” investigation that “reviews all payments you received, to make sure they didn’t originate with a sanctioned entity.” He added, “All the big four accounting companies do them routinely.” The Trump Organization did not commission a look-back.

The Baku deal appears to be the second time that the Trump Organization has turned a blind eye to U.S. efforts to sanction Iran. In 1998, when Donald Trump purchased the General Motors Building, in Manhattan, he inherited as a tenant Iran’s Bank Melli. The following year, the Treasury Department listed Bank Melli as an institution that was “owned or controlled” by the government of Iran and that was covered by U.S. sanctions. (The department later labelled Bank Melli one of the primary financial institutions through which Iran was funnelling money to finance terrorism and to develop weapons of mass destruction.) The Trump Organization kept Bank Melli as a tenant for four more years before terminating the lease.

Cartoon

“He says he loves me, but he still uses his first wife’s birthday as his password.”

JANUARY 30, 2012

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

The Baku project is hardly the only instance in which the Trump Organization has been associated with a controversial deal. The Trump Taj Mahal casino, which opened in Atlantic City in 1990, was repeatedly fined for violating anti-money-laundering laws, up until its collapse, late last year. According to ProPublica, Trump projects in India, Uruguay, Georgia, Indonesia, and the Philippines have involved government officials or people with close ties to powerful political figures. A few years ago, the Trump Organization abandoned a project in Beijing after its Chinese partner became embroiled in a corruption scandal. In December, the Trump Organization withdrew from a hotel project in Rio de Janeiro after it was revealed to be part of a major bribery investigation. Ricardo Ayres, a Brazilian state legislator, told Bloomberg, “It’s curious that the Trumps didn’t seem to know that their biggest deal in Brazil was bankrolled by shady investors.” But, given the Trump Organization’s track record, it seems reasonable to ask whether one of the things it was selling to foreign partners was a willingness to ignore signs of corruption.

To this day, the Trump Organization has not provided satisfying answers to the most basic questions about the Baku deal: who owns Baku XXI Century, the company with which they signed the contracts; the origin of the funds with which Baku XXI Century paid the Trump Organization; whether the Mammadovs used their political power to benefit themselves and the Trump Organization; and whether the Mammadovs used money obtained from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard to fund the Trump Tower Baku.

At one point, Garten allowed me to review the Trump Organization’s original contract with the Mammadovs. It authorizes the company to order an independent audit of Baku XXI Century’s financial records at any time—a provision likely included to insure that the Mammadovs didn’t hide profits that were supposed to be shared with the Trump Organization. Such an audit could well have exposed illicit activity. Garten refused to say if an audit had been conducted.

In dealing with the Mammadovs, the Trump Organization seems to have taken them entirely at their word. Garten pointed me to a provision in one contract in which Anar Mammadov represented himself as the sole owner of Baku XXI Century. Given that Elton Mammadov told me that he controlled the company, and that its ownership was a “commercial secret,” what proof did the Trump Organization have that Anar’s claim was true? Garten could not say.

Garten has been the company’s chief legal officer only since January. His predecessor was Jason Greenblatt, whose name appeared on the contract I reviewed. Greenblatt was in charge of the Trump Organization’s due diligence and contracting work. He is now employed at the White House, as the President’s special representative for international negotiations. He did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In recent months, American officials have expressed concern that Trump Administration figures might be blackmailed by foreign entities. U.S. law-enforcement investigators and congressional staffers have probed claims that Russian government officials possess compromising information about President Trump, which might be used to blackmail him. (The President maintains that there is no such information.) In January, the Department of Justice informed the White House that Michael Flynn—then the national-security adviser—was vulnerable to being blackmailed by the Russians because he had lied about having spoken with the Russian Ambassador. Flynn subsequently resigned.

In Azerbaijan, the power and the influence of the Mammadovs has declined sharply. Elton lost his seat in parliament in 2015. In February, Ziya was abruptly removed from his ministry. Anar has settled in London, an associate of his told me, and is living on a fraction of his former wealth. Meanwhile, in Iran, government officials are likely facing additional sanctions on the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. If the Mammadovs or powerful Iranians have evidence that the Trump Organization broke laws, they might be tempted to exploit it.

The best way to determine if a crime was committed in the Baku deal would be a federal investigation, which could use the power of subpoena and international legal tools to obtain access to the contracts, the due diligence, internal e-mails, and financial documents. The Department of Justice routinely sends investigators to other countries to pursue possible F.C.P.A. and sanctions violations.

Senator Sherrod Brown, of Ohio, who is the ranking Democratic member of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, said, in an e-mail, that a federal investigation was warranted: “The Trump Organization’s Baku project shows the lack of ‘extreme vetting’ Mr. Trump applied to his own business dealings in corruption-plagued regimes around the globe. . . . Congress—and the Trump Administration itself—has a duty to examine whether the President or his family is exposed to terrorist financing, sanctions, money laundering, and other imprudent associations through their business holdings and connections.”

More than a dozen lawyers with experience in F.C.P.A. prosecution expressed surprise at the Trump Organization’s seemingly lax approach to vetting its foreign partners. But, when I asked a former Trump Organization executive if the Baku deal had seemed unusual, he laughed. “No deal there seems unusual, as long as a check is attached,” he said.

|

| DONALD TRUMP’S WORST DEAL |

The building, a five-star hotel and residence called the Trump International Hotel & Tower Baku, has never opened, though from the road it looks ready to welcome the public. Reaching the property is surprisingly difficult; the tower stands amid a welter of on-ramps, off-ramps, and overpasses. During the nine days I was in town, I went to the site half a dozen times, and on each occasion I had a comical exchange with a taxi-driver who had no idea which combination of turns would lead to the building’s entrance.

The more time I spent in the neighborhood, the more I wondered how the hotel could have been imagined as a viable business. The development was conceived, in 2008, as a high-end apartment building. In 2012, after Donald Trump’s company, the Trump Organization, signed multiple contracts with the Azerbaijani developers behind the project, plans were made to transform the tower into an “ultra-luxury property.” According to a Trump Organization press release, a hotel with “expansive guest rooms” would occupy the first thirteen floors; higher stories would feature residences with “spectacular views of the city and Caspian Sea.” For an expensive hotel, the Trump Tower Baku is in an oddly unglamorous location: the underdeveloped eastern end of downtown, which is dominated by train tracks and is miles from the main business district, on the west side of the city. Across the street from the hotel is a discount shopping center; the area is filled with narrow, dingy shops and hookah bars. Other hotels nearby are low-budget options: at the AYF Palace, most rooms are forty-two dollars a night. There are no upscale restaurants or shops. Any guests of the Trump Tower Baku would likely feel marooned.

The timing of the project was also curious. By 2014, when the Trump Organization publicly announced that it was helping to turn the tower into a hotel, a construction boom in Baku had ended, and the occupancy rate for luxury hotels in the city hovered around thirty-five per cent. Jan deRoos, of Cornell University, who is an expert in hotel finance, told me that the developer of a five-star hotel typically must demonstrate that the project will maintain an average occupancy rate of at least sixty per cent for ten years. There is a long-term master plan to develop the area around the Trump Tower Baku, but if it is implemented the hotel will be surrounded for years by noisy construction projects, making it even less appealing to travellers desiring a luxurious experience—especially considering that there are many established hotels on the city’s seaside promenade. There, an executive from ExxonMobil or the Israeli cell-phone industry can stay at the Four Seasons, which occupies a limestone building that evokes a French colonial palace, or at the J. W. Marriott Abershon Baku, which has an outdoor terrace overlooking the water. Tiffany, Ralph Lauren, and Armani are among the dozens of companies that have boutiques along the promenade.

A former top official in Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Tourism says that, when he learned of the Trump hotel project, he asked himself, “Why would someone put a luxury hotel there? Nobody who can afford to stay there would want to be in that neighborhood.”

The Azerbaijanis behind the project were close relatives of Ziya Mammadov, the Transportation Minister and one of the country’s wealthiest and most powerful oligarchs. According to the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index, Azerbaijan is among the most corrupt nations in the world. Its President, Ilham Aliyev, the son of the former President Heydar Aliyev, recently appointed his wife to be Vice-President. Ziya Mammadov became the Transportation Minister in 2002, around the time that the regime began receiving enormous profits from government-owned oil reserves in the Caspian Sea. At the time of the hotel deal, Mammadov, a career government official, had a salary of about twelve thousand dollars, but he was a billionaire.

The Trump Tower Baku originally had a construction budget of a hundred and ninety-five million dollars, but it went through multiple revisions, and the cost ended up being much higher. The tower was designed by a local architect, and in its original incarnation it had an ungainly roof that suggested the spikes of a crown. A London-based architecture firm, Mixity, redesigned the building, softening its edges and eliminating the ornamental roof. By the time the Trump team officially joined the project, in May, 2012, many condominium residences had already been completed; at the insistence of Trump Organization staffers, most of the building’s interior was gutted and rebuilt, and several elevators were added.

After Donald Trump became a candidate for President, in 2015, Mother Jones, the Associated Press, the Washington Post, and other publications ran articles that raised questions about his involvement in the Baku project. These reports cited a series of cables sent from the U.S. Embassy in Azerbaijan in 2009 and 2010, which were made public by WikiLeaks. In one of the cables, a U.S. diplomat described Ziya Mammadov as “notoriously corrupt even for Azerbaijan.” The Trump Organization’s chief legal officer, Alan Garten, told reporters that the Baku hotel project raised no ethical issues for Donald Trump, because his company had never engaged directly with Mammadov.

Cartoon

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

According to Garten, Trump played a passive role in the development of the property: he was “merely a licensor” who allowed his famous name to be used by a company headed by Ziya Mammadov’s son, Anar, a young entrepreneur. It’s not clear how much money Trump made from the licensing agreement, although in his limited public filings he has reported receiving $2.8 million. (The Trump Organization shared documents that showed an additional payment of two and a half million dollars, in 2012, but declined to disclose any other payments.) Trump also had signed a contract to manage the hotel once it opened, for an undisclosed fee tied to the hotel’s performance. The Washington Post published Garten’s description of the deal, and reported that Donald Trump had “invested virtually no money in the project while selling the rights to use his name and holding the contract to manage the property.”

A month after Trump was elected President, Garten announced that the Trump Organization had severed its ties with the hotel project, describing the decision to CNN as little more than “housecleaning.” I was in Baku at the time, and it had become clear that the Trump Organization’s story of the hotel was incomplete and inaccurate. Trump’s company had made the deal not just with Anar Mammadov but also with Ziya’s brother Elton—an influential member of the Azerbaijani parliament. Elton signed the contracts, and in an interview he confirmed that he founded Baku XXI Century, the company that owns the Trump Tower Baku. When he was asked who owns Baku XXI Century, he called it a “commercial secret” but added that he “controlled all its operations” until 2015, when he cut ties to the company. Elton denied having used his political position for profit.

An Azerbaijani lawyer who worked on the project revealed to me that the Trump Organization had not just licensed the family name; it also had signed a technical-services agreement in which it promised to help its partner meet Trump design standards. Technical-services agreements are often nominal addenda to licensing deals. Major hospitality brands compile exhaustive specifications for licensed hotels, and tend to approve design elements remotely; a foreign site is visited only occasionally. But in the case of Trump Tower Baku the oversight appears to have been extensive. The Azerbaijani lawyer told me, “We were always following their instructions. We were in constant contact with the Trump Organization. They approved the smallest details.” He said that Trump staff visited Baku at least monthly to give the go-ahead for the next round of work orders. Trump designers went to Turkey to vet the furniture and fabrics acquired there. The hotel’s main designer, Pierre Baillargeon, and several contractors told me that they had visited the Trump Organization headquarters, in New York, to secure approval for their plans.

Ivanka Trump was the most senior Trump Organization official on the Baku project. In October, 2014, she visited the city to tour the site and offer advice. An executive at Mace, the London-based construction firm that oversaw the tower’s conversion to a hotel, met with Ivanka in Baku and New York. He told me, “She had very strong feelings, not just about the design but about the back of the hotel—landscaping, everything.” The Azerbaijani lawyer said, “Ivanka personally approved everything.” A subcontractor noted that Ivanka’s team was particular about wood panelling: it chose an expensive Macassar ebony, from Indonesia, for the ceiling of the lobby. The ballroom doors were to be made of book-matched panels of walnut. On her Web site, Ivanka posted a photograph of herself wearing a hard hat inside the half-completed hotel. A caption reads, “Ivanka has overseen the development of Trump International Hotel & Tower Baku since its inception, and she recently returned from a trip to the fascinating city in Azerbaijan to check in on the project’s progress.” (Ivanka Trump declined requests to discuss the Baku project.)

Jan deRoos, the Cornell professor, developed branded-hotel properties before entering academia. He told me that the degree of the Trump Organization’s involvement in the Baku property was atypical. “That’s very, very intense,” he said.

The sustained back-and-forth between the Trump Organization and the Mammadovs has legal significance. If parties involved in the Trump Tower Baku project participated in any illegal financial conduct, and if the Trump Organization exerted a degree of control over the project, the company could be vulnerable to criminal prosecution. Tom Fox, a Houston lawyer who specializes in anti-corruption compliance, said, “It’s a problem if you’re making a profit off of someone else’s corrupt conduct.” Moreover, recent case law has established that licensors take on a greater legal burden when they assume roles normally reserved for developers. The Trump Organization’s unusually deep engagement with Baku XXI Century suggests that it had the opportunity and the responsibility to monitor it for corruption.

Before signing a deal with a foreign partner, American companies, including major hotel chains, conduct risk assessments and background checks that take a close look at the country, the prospective partner, and the people involved. Countless accounting and law firms perform this service, as do many specialized investigation companies; a baseline report normally costs between ten thousand and twenty-five thousand dollars. A senior executive at one of the largest American hotel chains, who asked for anonymity because he feared reprisal from the Trump Administration, said, “We wouldn’t look at due diligence as a burden. There certainly is a cost to doing it, especially in higher-risk places. But it’s as much an investment in the protection of that brand. It’s money well spent.”

Alan Garten told me that the Trump Organization had commissioned a risk assessment for the Baku deal, but declined to name the company that had performed it. The Washington Post article on the Baku project reported that, according to Garten, the Trump Organization had undertaken “extensive due diligence” before making the hotel deal and had not discovered “any red flags.”

But the Mammadov family, in addition to its reputation for corruption, has a troubling connection that any proper risk assessment should have unearthed: for years, it has been financially entangled with an Iranian family tied to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, the ideologically driven military force. In 2008, the year that the tower was announced, Ziya Mammadov, in his role as Transportation Minister, awarded a series of multimillion-dollar contracts to Azarpassillo, an Iranian construction company. Keyumars Darvishi, its chairman, fought in the Iran-Iraq War. After the war, he became the head of Raman, an Iranian construction firm that is controlled by the Revolutionary Guard. The U.S. government has regularly accused the Guard of criminal activity, including drug trafficking, sponsoring terrorism abroad, and money laundering. Reuters recently reported that the Trump Administration was poised to officially condemn the Revolutionary Guard as a terrorist organization.

I asked Garten how deeply the Trump Organization had looked into the Mammadov family’s political connections. Had it been concerned that Elton Mammadov, as a sitting member of parliament, might exploit his power to benefit the project? How much money had Ziya Mammadov invested in Elton’s company? Garten noted that he didn’t oversee the due-diligence process. “The people who did are no longer at the company,” he said. “I can’t tell you what was done in this situation.” He would not identify the former employees. When I asked him to provide documentation of due diligence, he said that he couldn’t share it with me, because “it’s confidential and privileged.”

A 2014 Instagram post of Ivanka Trump at the Baku tower.

A 2014 Instagram post of Ivanka Trump at the Baku tower.

Photo Illustration by The New Yorker

No evidence has surfaced showing that Donald Trump, or any of his employees involved in the Baku deal, actively participated in bribery, money laundering, or other illegal behavior. But the Trump Organization may have broken the law in its work with the Mammadov family. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, passed in 1977, forbade American companies from participating in a scheme to reward a foreign government official in exchange for material benefit or preferential treatment. The law even made it a crime for an American company to unknowingly benefit from a partner’s corruption if it could have discovered illicit activity but avoided doing so. This closed what was known as the “head in the sand” loophole.

As a result, American companies must examine potential foreign partners very carefully before making deals with them. I recently spoke with Alexandra Wrage, who runs Trace International, a consortium of three hundred corporations that do business overseas. Trace helps these firms avoid violating the F.C.P.A., and it has a division that can be hired by individual clients to assess potential foreign partners. To comply with the law, Wrage noted, an American company must remain vigilant even after a contract is signed, monitoring its foreign partner to be sure that nobody involved is engaging in bribery or other improprieties.

Wrage pointed out that corrupt government leaders often use their children or their siblings to distance themselves from illicit projects. Such an official creates a company in the relative’s name which appears to be independent but is controlled by the official. To lessen the likelihood of an F.C.P.A. violation when working with a company that is owned by a child or a sibling of a government minister, Wrage told me, “you’d need to show that the child has real expertise, real ability to do the work.” Otherwise, Wrage said, “the assumption is that they are a partner entirely because of their ability to use their parent’s power.” Before Elton Mammadov became a member of parliament, in 2000, he was a maintenance engineer who had no experience in real-estate development. When the Trump Organization joined the Baku project, it barred a Mammadov-owned company from doing construction work, because it was deemed incompetent.

Wrage said that a U.S. company looking to make a deal with a foreign partner should be confident that the partner has a reasonable likelihood of making a profit from the venture. If the project seems almost guaranteed to lose money, it could well be a bribery scheme or some other criminal operation. The partner also should uphold modern accounting standards.

“It’s simple,” she said. “Will money flow through this business because it offers a compelling product at a decent price, or will the money come because of an illicit relationship with someone who uses their power?”

Wrage told me that, in 2009, an American entrepreneur was successfully prosecuted for his part in a corruption conspiracy in Azerbaijan. Frederic Bourke, the co-founder of Dooney & Bourke, the handbag company, had invested in a project in which a foreign partner paid bribes to Azerbaijani government officials and their family members. Bourke was sentenced to a year in prison for violating the F.C.P.A.; he appealed the conviction, claiming ignorance of the corruption. Two years later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the conviction, saying that, regardless of whether he had known about the bribes, “the testimony at trial demonstrated that Bourke was aware of how pervasive corruption was in Azerbaijan.” The F.C.P.A., they said, also criminalized “conscious avoidance”—a deliberate effort to remain in the dark about any transgressions a foreign partner might be involved in. After Bourke’s conviction, Wrage said, U.S. companies were well aware of the dangers of making careless deals in Azerbaijan.

Even a cursory look at the Mammadovs suggests that they are not ideal partners for an American business. Four years before the Trump Organization announced the Baku deal, WikiLeaks released the U.S. diplomatic cables indicating that the family was corrupt; one cable mentioned the Mammadovs’ link to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. In 2013, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project investigated the Mammadov family’s corruption and published well-documented exposés. Six months before the hotel announcement, Foreign Policy ran an article titled “The Corleones of the Caspian,” which suggested that the Mammadovs had exploited Ziya’s position as Transportation Minister to make their fortunes.

The Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty investigation revealed that Baku XXI Century, the company controlled by Elton, had at least two other stakeholders. One of them was a company called zqan, an acronym for the family members of the Transportation Minister: Ziya Mammadov; Qanira, his wife; Anar, his son; and Nigar, his daughter. Anar is the official head of zqan. Another stakeholder in Baku XXI Century was the Baghlan Group, a company run by an Azerbaijani businessman who is known to be close to Ziya Mammadov.

Baku XXI Century, zqan, and Baghlan have so many overlapping interests that they often seem to operate as a single concern. According to the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty investigation, the companies all prospered largely through contracts with the Transportation Ministry. The Trump Tower Baku complex was built partly on land controlled by the ministry. A Baghlan subsidiary received a contract from the ministry to import a thousand London-style cabs to Baku. Soon afterward, ministry inspectors began preventing competing taxi services from parking in the city center or at subway stops. Another new rule required all taxi owners to pay taxes and license fees at the Bank of Azerbaijan, a private entity that at the time was owned jointly by Anar Mammadov and Baghlan.

|

| DONALD TRUMP’S WORST DEAL |

One of the cables sent in 2010 by the U.S. Embassy in Baku noted that, “with so much of the nation’s oil wealth being poured into road construction,” the Mammadovs had become disproportionately powerful in Azerbaijan. Another cable suggested that Ziya controlled zqan, the country’s “largest commercial development company.” This cable described Ziya as being the object of “many allegations from Azerbaijani contacts of creative corrupt practices.”

Much of the land occupied by the Trump Tower Baku complex was once packed with houses. In 2011, residents received letters from the local government authority informing them that their homes were to be demolished to make way for a project of crucial government significance. Thirty families were evicted. One resident, Minaye Azizova, told me that the government gave her eighteen thousand dollars in compensation for a home that, by her estimation, was worth five times as much. After she discovered that her home had been condemned so that Baku XXI Century could build a luxury tower, she sued the government.

Cartoon

“Turns out the sound of the squeaky toy was coming from inside the house.”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

Construction of the building began in 2008. I have spoken with more than a dozen contractors who worked on it. Some of them described behavior that seemed nakedly corrupt. Frank McDonald, an Englishman who has had a long career doing construction jobs in developing countries, performed extensive work on the building’s interior. He told me that his firm was always paid in cash, and that he witnessed other contractors being paid in the same way. At the offices of Anar Mammadov’s company, he said, “they would give us a giant pile of cash,” adding, “I got a hundred and eighty thousand dollars one time, which I fit into my laptop bag, and two hundred thousand dollars another time.” Once, a colleague of his picked up a payment of two million dollars. “He needed to bring a big duffelbag,” McDonald recalled. The Azerbaijani lawyer confirmed that some contractors on the Baku tower were paid in cash.

Two people who worked on the Trump Tower Baku told me that bribes were paid. Much of the graft was routine: Azerbaijani tax officials, government inspectors, and customs officers showed up occasionally to pick up envelopes of cash.

The executive at Mace, the construction firm, told me that the Mammadovs handled payments and all interactions with the Azerbaijani government. “Were people bribed?” he said. “I don’t know. Maybe. We didn’t check.” (A spokesman for Mace said that the firm was “not involved” in any corruption.)

Pierre Baillargeon, the architect whom the Mammadovs hired to alter the tower’s original design, is a Canadian who runs a studio in London. He has often worked in parts of the world known for corruption, including Sudan and Syria, and has done several projects in Azerbaijan. In a phone interview, Baillargeon said that he knew nothing about corruption and was “just a designer.” I asked him why he thought the hotel had been built in such an inhospitable part of Baku. “Every project has detractors,” he said. When I asked him if he had seen large payments being made in cash, he hung up. (He did not respond to later calls.)

Alan Garten, the Trump Organization lawyer, did not deny that there was corruption involved in the project. “I’m not going to sit here and defend the Mammadovs,” he said. But, from a legal standpoint, he argued, the Trump Organization was blameless. In his opinion, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act doesn’t apply to the Baku deal, even if corruption occurred. “We didn’t own it,” he said of the hotel. “We had no equity. We didn’t control the project. The flow of funds is in the wrong direction.” He added, “We did not pay any money to anyone. Therefore, it could not be a violation of the F.C.P.A.”

“No, that’s just wrong,” Jessica Tillipman, an assistant dean at George Washington University Law School, who specializes in the F.C.P.A., said. “You can’t go into business deals in Azerbaijan assuming that you are immune from the F.C.P.A.” She added, “Nor can you escape liability by looking the other way. The entire Baku deal is a giant red flag—the direct involvement of foreign government officials and their relatives in Azerbaijan with ties to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. Corruption warning signs are rarely more obvious.”

Tillipman explained that the F.C.P.A. defines corruption as “the payment of money or anything of value” to a foreign official. Last year, JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay two hundred and sixty-four million dollars to settle charges that it had violated the F.C.P.A.; the bank had given jobs and internships to relatives and friends of government officials in Asia. Tillipman, along with several other F.C.P.A. experts, told me that the Trump Organization had clearly provided things of value in the Baku deal: its famous brand, its command of the luxury market, its extensive technical advice.

In May, 2012, the month the Baku deal was finalized, the F.C.P.A. was evidently on Donald Trump’s mind. In a phone-in appearance on CNBC, he expressed frustration with the law. “Every other country goes into these places and they do what they have to do,” he said. “It’s a horrible law and it should be changed.” If American companies refused to give bribes, he said, “you’ll do business nowhere.” He continued, “There is one answer—go to your room, close the door, go to sleep, and don’t do any deals, because that’s the only way. The only way you’re going to do it is the other way.”

It is unclear how the Trump Administration plans to approach F.C.P.A. enforcement. Jay Clayton, Trump’s choice to run the Securities and Exchange Commission, co-authored a paper in 2011 arguing that American companies were at a severe disadvantage because of the U.S. government’s “singular strategy of zealous enforcement.” But Jeff Sessions, the new Attorney General, told the Senate Judiciary Committee during his confirmation hearings that he will continue to uphold the F.C.P.A.

After 9/11, prosecuting financial corruption acquired new political importance. The C.I.A. and other intelligence services came to believe that preventing illicit money from flowing through the global financial system was a necessary tactic in preventing future terrorist attacks, and the U.S. led an international effort to enforce financial transparency. Banks and other financial entities were required to vet their clients aggressively and to report any suspicious activity. Prosecutions for money laundering, bribery, and other financial crimes rose significantly. In 2000, the government launched three prosecutions under the F.C.P.A. Last year, it initiated fifty-four.

Investigators of financial fraud like to say that government corruption, money laundering, and other illicit behavior often form a “nexus” with even more troubling activity, such as financing terrorism and developing weapons of mass destruction. This appears to be true in the Baku deal. As the Mammadovs were preparing to build the tower, the family patriarch, Ziya, was cementing his financial relationship with the Darvishis, the Iranian family with ties to the country’s Revolutionary Guard.

At least three Darvishis—the brothers Habil, Kamal, and Keyumars—appear to be associates of the Guard. In Farsi press accounts, Habil, who runs the Tehran Metro Company, is referred to as a sardar, a term for a senior officer in the Revolutionary Guard. A cable sent on March 6, 2009, from the U.S. Embassy in Baku described Kamal as having formerly run “an alleged Revolutionary Guard-controlled business in Iran.” The company, called Nasr, developed and acquired instruments, guidance systems, and specialty metals needed to build ballistic missiles. In 2007, Nasr was sanctioned by the U.S. for its role in Iran’s effort to develop nuclear missiles.

The cable said that Kamal and Keyumars were frequent visitors to Azerbaijan; Kamal had recently established “a close business relationship/friendship” with Ziya Mammadov, and, with Mammadov’s assistance, had been awarded “at least eight major road construction and rehabilitation contracts, including contracts for construction of the Baku-Iranian Astara highway.” (Keyumars also seems to have been involved in these deals.) The cable added, “We assume Mammedov [sic] is a silent partner in these contracts.”

Cartoon

“Does the No. 1 stop here and does that go to Penn Station and can I get a train there to Philadelphia and then how do I get to Walnut Street?”

JANUARY 10, 2011

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon