Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, young directors who go by the joint film credit Daniels, are known for reality-warped miniatures—short films, music videos, commercials—that are eerie yet playful in mood. In their work, people jump into other people’s bodies, Teddy bears dance to hard-core dubstep, rednecks shoot clothes from rifles onto fleeing nudists. Last year, their first feature-length project, “Swiss Army Man”—starring Daniel Radcliffe, who plays a flatulent talking corpse that befriends a castaway—premièred at Sundance, and left some viewers wondering if it was the strangest thing ever to be screened at the festival. The Times, deciding that the film was impossible to categorize, called it “weird and wonderful, disgusting and demented.”

Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, young directors who go by the joint film credit Daniels, are known for reality-warped miniatures—short films, music videos, commercials—that are eerie yet playful in mood. In their work, people jump into other people’s bodies, Teddy bears dance to hard-core dubstep, rednecks shoot clothes from rifles onto fleeing nudists. Last year, their first feature-length project, “Swiss Army Man”—starring Daniel Radcliffe, who plays a flatulent talking corpse that befriends a castaway—premièred at Sundance, and left some viewers wondering if it was the strangest thing ever to be screened at the festival. The Times, deciding that the film was impossible to categorize, called it “weird and wonderful, disgusting and demented.”Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that when the Daniels were notified by their production company, several years ago, that an Israeli indie pop star living in New York wanted to hire them to experiment with technology that could alter fundamental assumptions of moviemaking, they took the call.

The musician was Yoni Bloch, arguably the first Internet sensation on Israel’s music scene—a wispy, bespectacled songwriter from the Negev whose wry, angst-laden music went viral in the early aughts, leading to sold-out venues and a record deal. After breaking up with his girlfriend, in 2007, Bloch had hoped to win her back by thinking big. He made a melancholy concept album about their relationship, along with a companion film in the mode of “The Wall”—only to fall in love with the actress who played his ex. He had also thought up a more ambitious idea: an interactive song that listeners could shape as it played. But by the time he got around to writing it his hurt feelings had given way to more indeterminate sentiments, and the idea grew to become an interactive music video. The result, “I Can’t Be Sad Anymore,” which he and his band released online in 2010, opens with Bloch at a party in a Tel Aviv apartment. Standing on a balcony, he puts on headphones, then wanders among his friends, singing about his readiness to escape melancholy. He passes the headphones to others; whoever wears them sings, too. Viewers decide, by clicking on onscreen prompts, how the headphones are passed—altering, in real time, the song’s vocals, orchestration, and emotional tone, while also following different micro-dramas. If you choose the drunk, the camera follows her as she races into the bathroom, to Bloch’s words “I want to drink less / but be more drunk.” Choose her friend instead, and the video leads to sports fans downing shots, with the lyrics “I want to work less / but for a greater cause.”

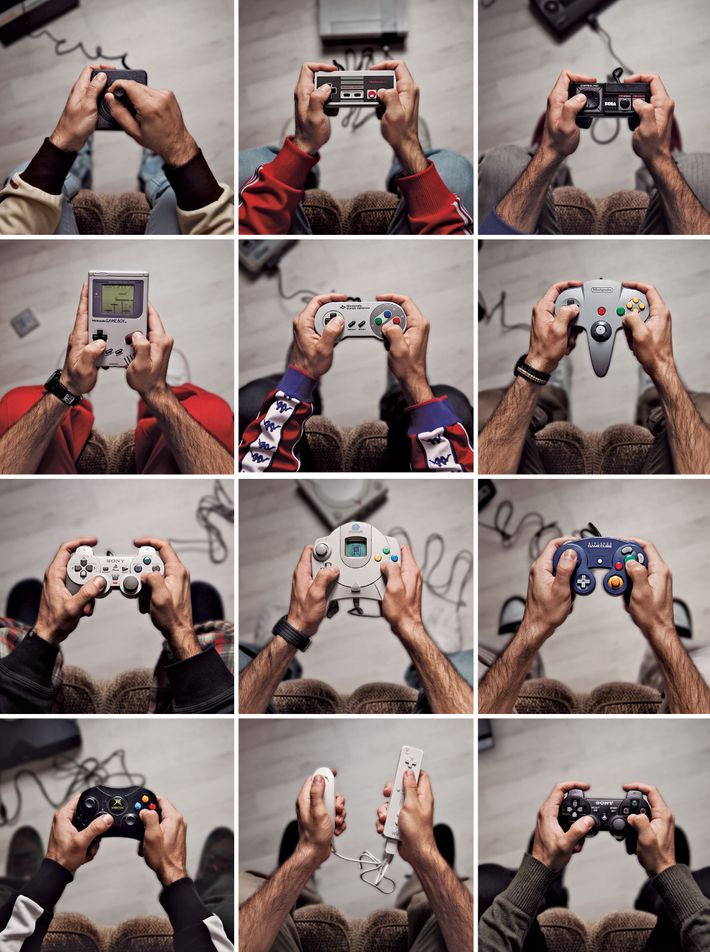

Bloch came to believe that there was commercial potential in the song’s underlying technology—software that he and his friends had developed during a few intense coding marathons. (Bloch had learned to write programs at an early age, starting on a Commodore 64.) He put his music career on hold, raised millions of dollars in venture capital, and moved to New York. Bloch called his software Treehouse and his company Interlude—the name hinting at a cultural gap between video games and movies which he sought to bridge. What he was selling was “a new medium,” he took to saying. Yet barely anyone knew of it. Treehouse was technology in need of an auteur, which is why Bloch reached out to the Daniels—encouraging them to use the software as they liked. “It was like handing off a new type of camera and saying, ‘Now, use this and do something amazing,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘I don’t want to tell you what to do.’ ”

Bloch was offering for film an idea that has long existed in literature. In 1941, Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story about a learned Chinese governor who retreated from civilization to write an enormous, mysterious novel called “The Garden of Forking Paths.” In Borges’s telling, the novel remained a riddle—chaotic, fragmentary, impenetrable—for more than a century, until a British Sinologist deciphered it: the book, he discovered, sought to explore every possible decision that its characters could make, every narrative bifurcation, every parallel time line. By chronicling all possible worlds, the author was striving to create a complete model of the universe as he understood it. Borges apparently recognized that a philosophical meditation on bifurcating narratives could make for more rewarding reading than the actual thing. “The Garden of Forking Paths,” if it truly explored every possible story line, would have been a novel without any direction—a paradox, in that it would hardly say more than a blank page.

Cartoon

“Part of me is going to miss liberal democracy.”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

Daniel Kwan told me that while he was in elementary school, in the nineteen-nineties, he often returned from the public library with stacks of Choose Your Own Adventure novels—slim volumes, written in the second person, that allow readers to decide at key moments how the story will proceed. (“If you jump down on the woolly mammoth, turn to page 29. If you continue on foot, turn to page 30.”) The books were the kind of thing you could find in a child’s backpack alongside Garbage Pail Kids cards and Matchbox cars. For a brief time, they could offer up a kind of Borgesian magic, but the writing was schlocky, the plot twists jarring, the endings inconsequential. As literature, the books never amounted to anything; the point was that they could be played. “Choose Your Own Adventure was great,” Kwan told me. “But even as a kid I was, like, there is something very unsatisfying about these stories.”

Early experiments in interactive film were likewise marred by shtick. In 1995, a company called Interfilm collaborated with Sony to produce “Mr. Payback,” based on a script by Bob Gale, who had worked on the “Back to the Future” trilogy. In the movie, a cyborg meted out punishment to baddies while the audience, voting with handheld controllers, chose the act of revenge. The film was released in forty-four theatres. Critics hated it. “The basic problem I had with the choices on the screen with ‘Mr. Payback’ is that they didn’t have one called ‘None of the above,’ ” Roger Ebert said, declaring the movie the worst of the year. “We don’t want to interact with a movie. We want it to act on us. That’s why we go, so we can lose ourselves in the experience.”

Gene Siskel cut in: “Do it out in the lobby—play the video game. Don’t try to mix the two of them together. It’s not going to work!”

Siskel and Ebert might have been willfully severe. But they had identified a cognitive clash that—as the Daniels also suspected—any experiment with the form would have to navigate. Immersion in a narrative, far from being passive, requires energetic participation; while watching movies, viewers must continually process new details—keeping track of all that has happened and forecasting what might plausibly happen. Good stories, whether dramas or action films, tend to evoke emotional responses, including empathy and other forms of social cognition. Conversely, making choices in a video game often produces emotional withdrawal: players are either acquiring skills or using them reflexively to achieve discrete rewards. While narratives help us to make sense of the world, skills help us to act within it.

As the Daniels discussed Bloch’s offer, they wondered if some of these problems were insurmountable, but the more they talked about them, the more they felt compelled to take on the project. “We tend to dive head first into things we initially want to reject,” Kwan said. “Interactive filmmaking—it’s like this weird thing where you are giving up control of a tight narrative, which is kind of the opposite of what most filmmakers want. Because the viewer can’t commit to one thing, it can be a frustrating experience. And yet we as human beings are fascinated by stories that we can shape, because that’s what life is like—life is a frustrating thing where we can’t commit to anything. So we were, like, O.K., what if we took a crack at it? No one was touching it. What would happen if we did?”

The Daniels live half a mile from each other, in northern Los Angeles, and they often brainstorm in informal settings: driveway basketball court, back-yard swing set, couch, office. After making an experimental demo for Bloch, they signed on for a dramatic short film. “Let us know any ideas you have,” Bloch told them. “We’ll find money for any weird thing.” By then, Interlude had developed a relationship with Xbox Entertainment Studios, a now defunct wing of Microsoft that was created to produce television content for the company’s game console. (The show “Humans,” among others, was first developed there.) Xbox signed on to co-produce.

While brainstorming, the Daniels mined their misgivings for artistic insight. “We’d be, like, This could suck if the audience was taken out of the story right when it was getting good—if they were asked to make a choice when they didn’t want to. And then we would laugh and be, like, What if we intentionally did that?” Scheinert told me. “We started playing with a movie that ruins itself, even starts acknowledging that.” Perhaps the clash between interactivity and narrative which Ebert had identified could be resolved by going meta—by making the discordance somehow essential to the story. The Daniels came up with an idea based on video-game-obsessed teen-agers who crash a high-school party. “We wanted to integrate video-game aesthetics and moments into the narrative—crazy flights of fancy that were almost abrasively interactive,” Scheinert said. “Because the characters were obsessed with gaming, we would have permission to have buttons come up in an intrusive and motivated way.”

Cartoon

“Your grass-fed beef—are the cows forced to eat the grass?”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

For other ideas, the two directors looked to previous work by Bloch’s company. Interlude had designed several simple games, music videos, and online ads for Subaru and J. Crew, among others, but the scope for interaction was limited. “It was, like, pick what color the girl’s makeup is, or, like, pick the color of the car and watch the driver drive around,” Scheinert recalled. One project that interested them was a music video for Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” While the song plays, viewers can flip among sixteen faux cable channels—sports, news, game shows, documentaries, dramas—but on each channel everyone onscreen is singing Dylan’s lyrics. The video attracted a million views within twenty-four hours, with the average viewer watching it three times in a row. The Daniels liked the restrained structure of the interactivity: instead of forking narratives, the story—in this case, the song—remained fixed; viewers were able to alter only the context of what they heard.

With this principle in mind, the Daniels came up with an idea for a horror film: five strangers trapped in a bar visited by a supernatural entity. “Each has a different take on what it is, and you as a viewer are switching between perspectives,” Kwan said. “One person thinks the whole thing is a prank, so he has a cynical view. One is religious and sees it as spiritual retribution. One sees it as her dead husband. The whole thing is a farcical misunderstanding of five characters who see five different things.”

Their third idea was about a romantic breakup: a couple wrestling with the end of their relationship as reality begins to fragment—outer and inner worlds falling apart in unison. “We got excited about it looking like an M. C. Escher painting,” Scheinert said. “We were playing with it getting frighteningly surreal. Maybe there’s, like, thousands of versions of your girlfriend, and one of them is on stilts, and one of them is a goth—”

“It was us making fun of the possible-worlds concept, almost—but that became overwhelming,” Kwan said.

“And so we started to zero in on our theme,” Scheinert said. “We realized, Oh, all the silliness is icing more than substance.” The premise was that the viewer would be able to explore different versions of the breakup but not alter the dialogue or the outcome. “We thought there was something funny about not being able to change the story—about making an interactive film that is thematically about your inability to change things.”

The Daniels submitted all three ideas—three radically different directions—for Bloch and his team to choose from. Then they waited.

Interlude operates from behind a metal security door on the sixth floor of a building off Union Square. The elevator opens into a tiny vestibule. On a yellow table is a wooden robot, alongside a stack of Which Way books—a copycat series in the style of Choose Your Own Adventure. A pane of glass reveals a bright office space inside: a lounge, rows of workstations, people who mostly postdate 1980.

Yoni Bloch occupies a corner office. Thin, smiling, and confident, he maintains a just-rolled-out-of-bed look. In summer, he dresses in flip-flops, shorts, and a T-shirt. Usually, he is at his desk, before a bank of flat-screen monitors. An acoustic guitar and a synthesizer sit beside a sofa, and above the sofa hangs a large neo-expressionist painting by his sister, depicting a pair of fantastical hominids.

Bloch’s world is built on intimate loyalties. He wrote his first hit song, in 1999, with his best friend in high school. He co-founded Interlude with two bandmates, Barak Feldman and Tal Zubalsky. Not long after I met him, he told me about the close bond that he had with his father, a physicist, who, starting at the age of nine, wrote in a diary every day: meticulous Hebrew script, filling page after page. After his father passed away, Bloch began reading the massive document and discovered a new perspective on conversations they had shared long before, experiences they had never spoken about. When he yearned to confer with his father about Interlude, he went looking for passages about the company; when his son was born, last year, he searched for what his father had written when his first child was born. Rather than read straight through, Bloch took to exploring the diary sporadically, out of time—as if probing a living memory.

Cartoon

“When he reached the end of the pier, the rhetoric turned nasty.”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

Treehouse is an intuitive program for a nonintuitive, nonlinear form of storytelling, and Bloch is adept at demonstrating it. In his office, he called up a series of video clips featuring the model Dree Hemingway sitting at a table. Below the clips, in a digital workspace resembling graph paper, he built a flowchart to map the forking narrative—how her story might divide into strands that branch outward, or loop backward, or converge. At first, the flowchart looked like a “Y” turned on its side: a story with just one node. “When you start, it is always ‘To be, or not to be,’ ” he said. The choice here was whether Hemingway would serve herself coffee or tea. Bloch dragged and dropped video clips into the flowchart, then placed buttons for tea and coffee into the frame, and set the amount of time the system would allow viewers to decide. In less than a minute, he was previewing a tiny film: over a soundtrack of music fit for a Philippe Starck lobby, Hemingway smiled and poured the beverage Bloch had selected. He then returned to the graph paper and added a blizzard of hypothetical options: “You can decide that here it will branch again, here it goes into a loop until it knows what to do, and here it becomes a switching node where five things can happen at the same time—and so on.”

As Bloch was getting his company off the ground, a small race was under way among like-minded startups looking for financial backing. In Switzerland, a company called CtrlMovie had developed technology similar to Interlude’s, and was seeking money for a feature-length thriller. (The film, “Late Shift,” had its American première last year, in New York.) Closer to home, there was Nitzan Ben-Shaul, a professor at Tel Aviv University, who, in 2008, had made an interactive film, “Turbulence,” using software that he had designed with students. Ben-Shaul, like the Daniels, felt some ambivalence about the form, even as he sought to develop it. “What I asked myself while making ‘Turbulence’ was: Why am I doing this?” he told me. “What is the added value of this, if I want to enhance the dramatic effect of regular movies?” The questions were difficult to answer. Some of his favorite films—“Rashomon,” for instance—prodded viewers to consider a story’s divergent possibilities without requiring interactivity. As a result, they maintained their coherence as works of art and, uncomplicated by the problems of audience participation, could be both emotionally direct and thought-provoking. “Rashomon” ’s brilliance, Ben-Shaul understood, was not merely the result of its formal inventiveness. Its director, Akira Kurosawa, had imbued it with his ideas about human frailty, truth, deceit, and the corrupting effects of self-esteem.

Ben-Shaul feared that, as technology dissolved the boundaries of conventional narrative, it could also interfere with essential elements of good storytelling. What was suspense, for example, if not a deliberate attempt to withhold agency from audience members—people at the edge of their seats, screaming, “Don’t go in there!,” enjoying their role as helpless observers? At the same time, why did the mechanisms of filmmaking have to remain static? Cautiously, he embraced the idea that interactivity could enable a newly pliant idea of cinematic narrative—“one that is opposed to most popular movies, which are built on suspense, which make you want to get to the resolution, and focus you on one track, one ending.” Perhaps, he thought, such films could even have a liberating social effect: by compelling audiences to consider the multiplicity of options a character could explore, and by giving them a way to act upon those options, movies could foster a sense of open-mindedness and agency that might be carried into the real world. He began pitching his technology to investors.

Yoni Bloch and his bandmates, meanwhile, were lining up gigs in the Pacific Northwest to pay for a flight from Tel Aviv, to present Treehouse to Sequoia Capital, the investment firm. The trip had grown out of a chance meeting with Haim Sadger, an Israeli member of the firm, who had handed Bloch his business card after seeing a demo of “I Can’t Be Sad Anymore” at a technology convention in Tel Aviv. Bloch, who hadn’t heard of Sequoia and thought it sounded fly-by-night, filed the card away. But, once the significance of the interest was explained to him, he worked to get his band to the group’s headquarters, in Menlo Park, California.

Bloch speaks with a soft lisp, and in a tone that betrays no urgency to monetize, but he is a skilled pitchman. Once, he gave a presentation to a Hollywood director who was recovering from a back injury and had to stand. “Even if you’re standing and he’s sitting, it feels the other way round,” the director recalled. “He owns the room.” Sadger told me that three minutes into his presentation Bloch had everyone’s attention. Coming from the worlds of music videos and video games, rather than art films, Bloch and his band spoke earnestly, and with little hesitancy, about revolutionizing cinematic narratives. “They didn’t see at the time the tremendous business potential that their creative idea and evolving technology had,” Sadger said. The Sequoia investors recognized a business that could not only earn revenue by licensing the technology but also harvest data on viewer preferences and support new advertising models; they offered Bloch and his bandmates more than three million dollars. “They beat us in getting large investments,” Ben-Shaul recalled. “Our investment fell through—and they took off.”

Cartoon

“There are no seats left together, but maybe if you make pouty faces at me I can magically add more chairs to the airplane.”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

By the time Bloch moved to New York, in 2011, and contacted the Daniels, Interlude had raised an additional fifteen million dollars in venture capital. Bloch told the directors that if there were creative options that Treehouse did not provide he could build them. The role of enabler comes naturally to him. (His best songs, a critic at Haaretz told me, were those he had written and produced for other people.) Bringing a music producer’s sense of discrimination to video, Bloch told the Daniels that they should make the breakup story. “Right away, it was, like, Let’s go with the hardest concept,” he told me. “Love stories have been written billions of times, especially love tragedies. It’s the oldest story in the book. Finding out how to make it different while using the audience is something you can’t do easily.”

“Possibilia” is a term of art in metaphysics, and it is also the title that the Daniels placed on the cover sheet of a six-page treatment for their breakup film—alongside mug shots of twenty-three uniformed schoolgirls, each with an orange on her shoulder. The schoolgirls don’t signify anything, except, perhaps, that the remaining pages are going to get weird, and that a serious idea will be toyed with.

In the treatment, the Daniels sketched out a cinematic poem: a brief investigation of indecision and emotional entropy in a dissolving romance. The story starts with a couple, Rick and Polly, seated at a kitchen table. They begin to argue, and, as they do, reality begins to unravel. Soon, their breakup is unfolding across parallel worlds that divide and multiply: first into two, then four, eight, sixteen. The Daniels envisioned viewers using thumbnails to flip among the alternate realities onscreen.

Translating the treatment into a script posed a unique challenge: because the dialogue needed to be identical across the sixteen different performances, so that viewers could shift from one to another seamlessly, Rick’s and Polly’s lines had to be highly general. “Early on, we came up with all sorts of specific lines, and they kept falling by the wayside, because we couldn’t come up with different ways to interpret them,” Scheinert said. “It got vaguer the harder we worked on it, which is the opposite of good screenwriting.” Kwan added, “Basically, we allowed the location, the performance, and the actions to give all the specificity.”

close dialog

To get more of the latest

stories from The New Yorker,

sign up for our newsletter.

Enter your e-mail address.

Get access.

At one moment of tension, as the film splinters into eight parallel worlds, Polly declares, “I need to do something drastic!” The script notes that her line will be delivered, variously, in the kitchen, in a laundry room, on the stairs, in a doorway, on the porch, in the front and back yards, and on the street—and that in each setting she will make good on her outburst differently: “slaps him and starts a fight / starts making out with him / flips the table / breaks something / gets in a car and begins to drive away / etc.” Like a simple melody harmonized with varied chords, the story would change emotional texture in each world. To keep track of all the permutations, the Daniels used a color-coded spreadsheet.

The Daniels cast Alex Karpovsky (of “Girls”) and Zoe Jarman (of “The Mindy Project”) as Rick and Polly, and then recorded the two actors improvising off the script. “We kind of fell in love with their mumbly, accidental, awkward moments,” Scheinert said. But these “accidents,” like the written dialogue, would also have to be carefully synchronized across the many possible versions of the story. The Daniels edited the improvisations into an audio clip and gave it to the actors to memorize. Even so, to keep the timing precise, the actors had to wear earpieces during shooting—listening to their original improvisation, to match their exact rhythm, while interpreting the lines differently. “At first, it was very disorienting,” Karpovsky told me. “I had to keep the same pace, or the whole math at Interlude would fall apart: this section has to last 8.37 seconds, or whatever, so it seamlessly feeds into the next branch of our narrative.”

The result, empathetic and precise, could easily work as a gallery installation. The multiple worlds lend a sense of abstraction; the vagueness of the lines lends intimacy. As Scheinert told me, “It reminded me of bad relationships where you have a fight and you are, like, What am I saying? We are not fighting about anything.” While working on “Possibilia,” the Daniels decided to make the story end in the same place that it begins, dooming Rick and Polly to an eternal loop. Watching the film, toggling among the alternate worlds while the characters veer between argument and affection, one has the sense of being trapped in time with them. There is almost no narrative momentum, no drive to a definite conclusion, and yet the experience sustains interest because viewers are caught in the maelstrom of the couple’s present.

Cartoon

“No one designs for cat bodies.”

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

As a child, reading Choose Your Own Adventure books, I often kept my fingers jammed in the pages, not wanting to miss a pathway that might be better than the one I had chosen. In “Possibilia” there is no such concern, since all the pathways lead to the same outcome. The ability to wander among the alternate worlds serves more as a framing device, a set of instructions on how to consider the film, than as a tool for exhaustive use. “Possibilia” is only six minutes long, but when a member of Interlude roughly calculated the number of different possible viewings, he arrived at an unimaginably large figure: 3,618,502,788,666,131,106,986,593,281,521,497,120,414,687,020,801,267,626, 233,049,500,247,285,301,248—more than the number of seconds since the Big Bang. It is unfeasible to watch every iteration, of course; knowing this is part of the experience. By the time I spoke with Karpovsky, I had watched “Possibilia” a dozen times. He gleefully recalled a moment of particular intensity—“I got to light my hand on fire!”—that I hadn’t yet seen.

The film, in its structure, had no precedent, and one’s response to it seemed to be at least partly a function of age and technological fluency. When a screening of the project was arranged for Xbox, the studio’s head of programming, Nancy Tellem—a former director of network entertainment at CBS—was uncertain what to do. “I was sitting at a table with my team, and my natural response was to sit back and say, ‘O.K., I want to see the story,’ ” she told me. “But then, all of a sudden, my team, which is half the age that I am, starts screaming, ‘Click! Click! Click!’ ”

In 2014, a version of the film hit the festival circuit, but it quickly became impossible to see. Just after its début, Microsoft shuttered Xbox Entertainment Studios, to reassert a focus on video games—stranding all its dramatic projects without distribution. Last August, Interlude decided to make “Possibilia” viewable online, and I stopped by to watch its producers prepare it for release. Alon Benari, an Israeli director who has collaborated with Bloch for years, was tweaking the film’s primary tool: a row of buttons for switching among the parallel worlds. The system took a few seconds to respond to a viewer’s choice. “A lot of people were clicking, then clicking again, because they didn’t think anything happened,” he told me. “At the moment that viewers interact, it needs to be clear that their input has been registered.” He was working on a timer to inform a viewer that a decision to switch between worlds was about to be enacted. Two days before “Possibilia” went online, Benari reviewed the new system.

“Is it good?” Bloch asked him.

“Yeah,” Benari said. “I was actually on the phone with Daniel, and he was happy.” All that was left was the advertising. Interlude had secured a corporate partnership with Coke, and Benari was working on a “spark”—five seconds of footage of a woman sipping from a bottle, which would play before the film. Watching the ad, he said, “The visuals are a bit too clean, so with the audio we are going to do something a bit grungy.” After listening to a rough cut, he walked me to the door. He was juggling several new projects. He had recently shown me a pilot for an interactive TV show, its mood reminiscent of “Girls.” The interactivity was light; none of the forking pathways significantly affected the plot. Benari thought that there was value in the cosmetic choices—“You still feel a sense of agency”—but he was hoping for more. Wondering if the director was simply having trouble letting go, he said, “We like the storytelling, and the acting, but we feel he needs to amp up the use of interactivity.”

Trying to invent a new medium, it turns out, does not easily inspire focus. Early on, Interlude applied its technology to just about every form of visual communication: online education, ads, children’s programming, games, music videos. But in the past year Bloch has steered the company toward dramatic entertainment. After Microsoft shut down Xbox Entertainment Studios, he invited Nancy Tellem to serve as Interlude’s chief media officer and chairperson. Tellem, impressed by the way Interlude viewers tended to replay interactive content, accepted. “The fact that people go back and watch a video two other times—you never see it in linear television,” she told me. “In fact, in any series that you might produce, the hope is that the normal TV viewer will watch a quarter of it.” Interactive films might have seemed like a stunt in the nineties, but for an audience in the age of Netflix personalized content has become an expected norm; L.C.D. screens increasingly resemble mirrors, offering users opportunities to glimpse themselves in the content behind the tempered glass. Employees at Bloch’s company envision a future where viewers gather around the water cooler to discuss the differences in what they watched, rather than to parse a shared dramatic experience. It is hard not to see in this vision, on some level, the prospect of entertainment as selfie.

Cartoon

APRIL 2, 2007

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

Six months after Tellem was hired, Interlude secured a deal with M-G-M to reboot “WarGames,” the nineteen-eighties hacker film, as an interactive television series. (M-G-M also made an eighteen-million-dollar investment.) Last April, CBS hired Interlude to reimagine “The Twilight Zone” in a similar way, and in June Sony Pictures made a multimillion-dollar “strategic investment.” By August, Interlude was sitting on more than forty million dollars in capital—the money reflecting the growing industry-wide interest. (Steven Soderbergh recently completed filming for a secretive interactive project at HBO.) Business cards from other networks, left behind in Bloch’s office like bread crumbs, suggested additional deals in the making; a whiteboard listing new projects included a pilot for the N.B.A. To signify the corporate transformation, Bloch told me, his company had quietly changed its name, to Eko.

“As of when?” I asked.

“As of four days ago,” he said, smiling.

Even as the company was expanding, Bloch was striving to preserve a sense of scrappy authenticity. “We are a company run by a band,” he insisted. “Everything sums up to money—I have learned this—but we still believe that if you make the work about the story it will be powerful.” One of Eko’s creative directors was overseeing a grass-roots strategy to attract talent, giving seminars at universities and conferences, encouraging people to use the software, which is available for free online. Hundreds of amateurs have submitted films. The best of them have been invited to make actual shows.

Of the marquee projects, “WarGames” is the furthest along in development, with shooting scheduled to begin this winter. When Bloch’s team pitched M-G-M, they had in mind a project tied to the original film, which is about a teen-age hacker (Matthew Broderick) who breaks into a military server and runs a program called Global Thermonuclear War. He thinks the program is a game, but in fact it helps control the American nuclear arsenal, and soon he must reckon with the possibility that he has triggered a real nuclear war.

Sam Barlow, the Eko creative director overseeing the reboot, worked in video-game design before Bloch hired him. He told me, “The premise in the pitch was that there is a game, a literal game, that you are playing, and then—as with the original—it becomes apparent that there is a more nefarious purpose behind it. The idea was that you would be able to see the reaction to what you are doing as live-action video.”

This proposal was soon set aside, however, out of fear that toggling between a game and filmed segments would be jarring. Instead, Barlow pulled together a new pitch. Hacking was still central, but it would be explored in the present-day context of groups like Anonymous, and in the murky post-Cold War geopolitical environment: terrorism, drone warfare, cyber attacks. The story centered on a young hacker and her friends and family. Viewers would be seated before a simulacrum of her computer, viewing the world as she does, through chat screens, Skype-like calls, live streams of cable news. On a laptop, Barlow loaded a prototype: three actors chatting in separate video windows on a neutral background. With quick swipes, he moved one window to the foreground. The show’s internal software, he said, would track the feeds that viewers watched, noting when they took an interest in personal relationships, for instance, or in political matters. The tracking system would also gauge their reactions to the protagonist, to see if they preferred that her actions have serious consequences (say, putting lives at risk) or prankish ones (defacing an official Web site).

“Suppose you have a significant story branch,” Barlow said. “If that’s linked to an explicit decision that the viewer must make, then it feels kind of mechanical and simple.” In contrast, the show’s system will be able to customize the story seamlessly, merely by observing what viewers decide to watch. This design acknowledged that key life choices are often not guided by explicit decisions but by how we direct our attention—as Iris Murdoch once noted, “At crucial moments of choice most of the business of choosing is already over.” Before an impending story branch, for instance, the system would know if a particular viewer was interested in the protagonist’s personal life, and her serious side, and could alter the story accordingly—perhaps by killing off a close relative and having her seek revenge.

Barlow was uncertain how much of the “WarGames” tracking mechanics he should reveal to the viewer. “The two-million-dollar question is: Do we need to show this?” he said. He believed that interactive films will increasingly resemble online ads: unobtrusively personalized media. “When ads first started tracking you, for the first few months you’d be, like, ‘How did they know?’ A couple of months later, you’d be, like, ‘Of course they knew. I was Googling baby formula.’ And now it’s, like, ‘I’m still getting spammed for vacation properties around Lake Placid, and I’m, like, Dude, we went. You should already know!’ ”

Cartoon

“Freshly ground pepper?”

APRIL 1, 2013

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

In many ways, the swiping system that Barlow had designed was a work-around for technological limitations that will soon fall away. Advances in machine learning are rapidly improving voice recognition, natural-language processing, and emotion detection, and it’s not hard to imagine that such technologies will one day be incorporated into movies. Brian Moriarty, a specialist in interactive media at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, told me, “Explicit interactivity is going to yield to implicit interactivity, where the movie is watching you, and viewing is customized to a degree that is hard to imagine. Suppose that the movie knows that you’re a man, and a male walks in and you show signs of attraction. The plot could change to make him gay. Or imagine the possibilities for a Hitchcock-type director. If his film sees you’re noticing a certain actor, instead of showing you more of him it shows you less, to increase tension.”

Moriarty believes that as computer graphics improve, the faces of actors, or even political figures, could be subtly altered to echo the viewer’s own features, to make them more sympathetic. Lifelike avatars could even replace actors entirely, at which point narratives could branch in nearly infinite directions. Directors would not so much build films around specific plots as conceive of generalized situations that computers would set into motion, depending on how viewers reacted. “What we are looking at here is a breakdown in what a story even means—in that a story is defined as a particular sequence of causally related events, and there is only one true story, one version of what happened,” Moriarty said. With the development of virtual reality and augmented reality—technology akin to Pokémon Go—there is no reason that a movie need be confined to a theatrical experience. “The line between what is a movie and what is real is going to be difficult to pinpoint,” he added. “The defining art form of the twenty-first century has not been named yet, but it is something like this.”

In mid-October, Bloch showed me a video that demonstrates the cinematic use of eye tracking—technology that is not yet commercially widespread but will likely soon be. The Daniels had directed the demo, and they had imbued it with their usual playfulness. It opens on a couple in a café. Behind them, a woman in a sexy dress and a muscleman walk in; whichever extra catches your gaze enters the story. Throughout, an announcer strives to describe the tracking system, but the story he uses as a showcase keeps breaking down as the characters, using a magical photo album, flee him by escaping into their past. Viewers, abetting the couple, send them into their memories by glancing at the photos in their album. At key moments, the story is told from the point of view of the actor you watch the most. “People start out looking at both, and then focus on one—and it is not necessarily the one who talks,” Bloch said. “When you look at her, she talks about him, then you care about him.”

The future that the demo portended—entertainment shaped by deeply implicit interactivity—was one that the Daniels later told me they found exhilarating and disconcerting. “In some ways, as artists, we are supposed to be creating collective experiences,” Kwan said. “This could get really messy if what we are actually doing is producing work that creates more isolated experiences.” Alternatively, it is possible to imagine the same technology pulling audiences into highly similar story patterns—narratives dominated by violence and sex—as it registers the basest of human responses.

“On the upside, interactivity has the potential to push you to reflect on your biases,” Scheinert said. Psychological experiments suggest that people who inhabit digital avatars of a race, gender, or age unlike their own can become more empathetic. “Done right, interactivity can shed light on what divides us,” he added. “We find ourselves talking a lot about video games lately. Video games have blossomed into an art form that’s become pretty cool. People are now making interactive stories that can move you, that can make you reflect on your own choices, because they make you make the kinds of choices that a hero really has to make. At the same time, it is really hard to make films with multiple endings, and I wonder what shortcuts will present themselves, what patterns. Right now, we don’t have many to fall back on.”

On the morning that Bloch showed me the eye-tracking demo, the Eko offices were humming with anticipation. Two weeks earlier, the company had been divided into ten teams that competed, in a two-day hackathon, to produce mockups for new shows or games. The competition was a search for effective ways to tell stories in a new medium. The solution that the Daniels had worked out for “Possibilia”—a fixed narrative playing out across multiple worlds—might have sufficed for a short film, where abstract dialogue could be tolerated, but it was not scalable to feature-length projects. That morning, an Eko creative director told me that he was wrestling with the magnitude of the creative shift. “What does character development even mean if a viewer is modifying the character?” he said. If a film has five potential endings, does it constitute a single work of art, or is it an amalgam of five different works?

All the teams had completed their mini films, and Bloch, in his office, was ready to announce the winner. An employee knocked on his door. “Should I yalla everyone?” he asked—using the Arabic term for “Let’s go.”

“Yalla everyone,” Bloch said.

Cartoon

“It’s made entirely out of rejected résumés.”

JANUARY 22, 2007

ShareTweetBuy a cartoon

In the office cafeteria, there was a long wooden table, beanbag chairs, a drum kit. People munched on popcorn. On a flat-screen monitor, the staff of Eko’s Israeli satellite office, which does the technical work, had video-conferenced in. Bloch held a stack of envelopes, as if he were at the Oscars, and began to run through the submissions. Two groups had used voice recognition, making it possible to talk to their films. Others had toyed with “multiplayer” ideas. Sam Barlow’s team had filmed a man in Hell trying to save his life in a game of poker. Viewers play the role of Luck, selecting the cards being dealt—not to win the game but to alter the drama among the players. Bloch said he had cited the film in a recent presentation as a possibility worth exploring. “The expected thing in that kind of story is that you would be the guy who comes to Hell,” he said. “Playing Luck—something that is more godlike—is much more exciting.”

The winner, Bloch announced, was “The Mole,” in which the viewer plays a corporate spy. The team had written software that made it possible to manipulate objects in the film—pick them up and move them. Bloch thought the software had immediate commercial potential. Walking back to his office, he expressed his excitement about what it would mean to permanently alter a scene: to tamper with evidence in a crime drama, say, and know that the set would stay that way. “It makes the world’s existence more coherent,” he said.

Even as a number of Bloch’s creative directors were working to make the interactivity more implicit, he did not think that explicit choices would fade away. Done well, he believed, they could deepen a viewer’s sense of responsibility for a story’s outcome; the problem with them today was the naïveté of the execution, but eventually the requisite artistic sophistication would emerge. “Every time there is a new medium, there’s an excessive use of it, and everyone wants to make it blunt,” he told me. “When stereo was introduced—with the Beatles, for example—you could hear drums on the left, singing on the right, and it didn’t make sense musically. But, as time went on, people started to use stereo in ways that enhanced the music.” Bloch had started assembling a creative board—filmmakers, game designers, writers—to think about such questions. “We have to break out of the gimmicky use of interactivity, and make sure it is used to enhance a story. We are in the days of ‘Put the drums on the left.’ But we’re moving to where we don’t have to do that. People, in general, are ready for this.”