The shocking theft of the Mona Lisa, in August 1911, appeared to have been solved 28 months later, when the painting was recovered. In an excerpt from their new book, the authors suggest that the audacious heist concealed a perfect—and far more lucrative—crime.

It was a Monday and the Louvre was closed. As was standard practice at the museum on that day of the week, only maintenance workers, cleaning staff, curators, and a few other employees roamed the cavernous halls of the building that was once the home of France’s kings but for centuries had been devoted to housing the nation’s art treasures.

Also on VF.com: How Jacqueline Kennedy brought the Mona Lisa to America. Read “The Two First Ladies,” by Margaret Leslie Davis.

Also on VF.com: How Jacqueline Kennedy brought the Mona Lisa to America. Read “The Two First Ladies,” by Margaret Leslie Davis.Photograph by Lewandowski/LeMage/Gattelet/Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, N.Y.

Acquired through conquest, wealth, good taste, and plunder, those holdings were splendid and vast—so much so that the Louvre could lay claim to being the greatest repository of art in the world. With some 50 acres of gallery space, the collection was too immense for visitors to view in a day or even, some thought, in a lifetime. In the Salon Carré—the “square room”—alone could be seen two paintings by Leonardo da Vinci, three by Titian, two by Raphael, two by Correggio, one by Giorgione, three by Veronese, one by Tintoretto, and—representing non-Italians—one each by Rubens, Rembrandt, and Velázquez.

News. Hollywood. Style. Culture.

For more high-profile interviews, stunning photography, and thought-provoking features, subscribe now to Vanity Fair magazine.

But even in that collection of masterpieces, one painting stood out from the rest. As the Louvre’s maintenance director, a man named Picquet, passed through the Salon Carré during his rounds on the morning of August 21, 1911, he pointed out Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, telling a co-worker that it was the most valuable object in the museum. “They say it is worth a million and a half,” Picquet remarked, glancing at his watch as he left the room. The time was 7:20 a.m.

Shortly after Picquet departed the Salon Carré, a door to a storage closet opened and at least one man—for it would never be proved whether the thief worked alone—emerged. He had been in there since the previous day—Sunday, the museum’s busiest. Just before closing time, the thief had slipped inside the little closet so that he could emerge in the morning without the need to identify himself to a guard at the entrance.

There were many such small rooms and hidden alcoves within the ancient building; museum officials later confessed that no one knew how many. This particular room was normally used for storing easels, canvases, and art supplies for students who were engaged in copying the works of the old masters. The only firm anti-forgery requirement the museum imposed was that the reproductions could not be the same size as the original.

Emerging from the closet in a white artist’s smock, the intruder might have been mistaken for one of these copyists—or, perhaps, for a member of the museum’s maintenance staff, who also wore such smocks, in a practice intended to demonstrate that they were superior to other workers. If anyone noticed the thief, he would likely be taken for another of the regular museum employees.

As he entered the Salon Carré, the thief headed straight for the Mona Lisa. Lifting down the painting and carrying it into an enclosed stairwell nearby was no easy job. The painting itself weighs approximately 18 pounds, since Leonardo painted it not on canvas but on three slabs of wood, a fairly common practice during the Renaissance. A few months earlier, the museum’s directors had taken steps to physically protect the Mona Lisa by reinforcing it with a massive wooden brace and placing it inside a glass-fronted box, adding 150 pounds to its weight. The decorative Renaissance frame brought the total to nearly 200 pounds. However, only four sturdy hooks held it there, no more securely than if it had been hung in the house of a bourgeois Parisian. Museum officials would later explain that the paintings were fastened to the wall in this way to make it easy for guards to remove them in case of fire.

Once safely out of sight behind the closed door of the stairwell, the thief quickly stripped the painting of all its protective “garments”—the brace, the glass case, and the frame. Since the *Mona Lisa’*s close-grained wood, an inch and a half thick, made it impossible to roll up, he slipped the work underneath his smock. Measuring approximately 30 by 21 inches, it was small enough to avoid detection.

Though evidently familiar with the layout of the museum, the thief made one crucial mistake in his planning. At the bottom of the enclosed stairway that led down to the first floor of the Louvre was a locked door. The thief had obtained a key, but now it failed to work. Desperately, as he heard footsteps coming from above, he used a screwdriver to remove the doorknob.

Down the stairs came one of the Louvre’s plumbers, named Sauvet. Later, Sauvet—the only person to witness the thief inside the museum—testified that he had seen only one man, dressed as a museum employee. The man complained that the doorknob was missing. Apparently thinking that there was nothing strange about the situation, Sauvet produced a pliers to open the door. The plumber suggested that they leave it open in case anyone else should use the staircase. The thief agreed, and the two parted ways.

The door opened onto a courtyard, the Cour du Sphinx. From there the thief passed through another gallery, then entered the Cour Visconti, and—perhaps trying not to appear in a hurry—headed toward the main entrance of the museum. Few guards were on duty that day, and only one was assigned to that entrance. As luck would have it, the guard had left his post to fetch a bucket of water to clean the vestibule. He never saw the thief, or thieves, leave the building.

One passerby noticed a man on the sidewalk carrying a package wrapped in white cloth. The witness recalled noticing the man throw a shiny metal object into the ditch along the edge of the street. The passerby glanced at it—it was a doorknob.

Inside the museum, all was serene and would remain so for quite some time. At 8:35 a.m., Picquet passed through the Salon Carré again and noted that the painting was gone. He thought little of it at the time, since the museum’s photographers freely removed objects without notice and took them to a studio elsewhere in the building. Indeed, Picquet even remarked to his workers, “I guess the authorities have removed it because they thought we would steal it!”

If anyone else noticed during the rest of the day that there were four bare hooks where the Mona Lisa usually hung, they kept it to themselves. Incredibly, not until Tuesday, when the Louvre again opened its doors to the public, did anyone express concern over the fact that the world’s most famous painting was missing from its usual place. When an artist set up his easel in the Salon Carré and noticed that the centerpiece of his intended work was absent, he complained to a guard, who merely shrugged. Like Picquet the day before, the guard assumed the Mona Lisa had been removed to the photographers’ studio. But the artist persisted. How soon would it be returned?

The guard finally went to see a photographer, who denied having anything to do with the painting. Perhaps it had been taken by a curator for cleaning? No. Finally, the guard thought it wise to inform a superior. A search began and soon became frantic. The director of the museum was on vacation, so the unthinkable news filtered up to the acting head, Georges Bénédite: Elle est partie! She’s gone.

“Paris Has Been Startled”

Lisa Gherardini, who married Francesco del Giocondo of Florence at age 16, would have been in her mid-20s when she sat for her portrait with Leonardo da Vinci in 1503. Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa—or La Joconde, as she is known in France—for four years, but like so many of his works, the painting was never completed. However, it had already achieved fame by the mid–16th century, owing to the innovations that had gone into its production—particularly in material, brush technique, and varnish—and its subject’s famously coy smile, which is said to be the result of musicians and clowns the artist kept on hand to prevent her from growing bored.

When Leonardo traveled to France around 1517, at the invitation of King Francis I, the Mona Lisa left Italy, it seemed, forever. The artist died only two years later, and by the middle of that century the painting—purchased for a considerable sum—had entered the collection of the French monarchy. Louis XIV gave the Mona Lisa a place of honor in his personal gallery at Versailles. But his successor, Louis XV, sent the painting to hang ignominiously in the office of the keeper of the royal buildings. However, in 1797, La Joconde was chosen as one of the works displayed in the nation’s new art museum, the Louvre, which is where she remained—save a brief stay in Napoleon’s bedroom—until someone carried her off in August 1911.

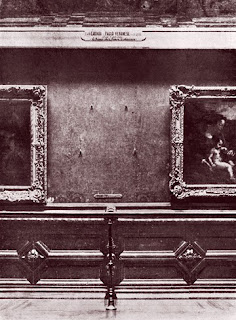

The Louvre, after the Mona Lisa was stolen, May 1912. From Mirrorpix.

Paris during the Belle Époque—the “beautiful time” between the late 19th century and the outbreak of World War I—had become an international center for painting, dance, music, theater, and publishing. The construction of Gustav Eiffel’s tower for the 1889 world’s fair had made it the “city of light”—both literally and metaphorically. The city could boast many of the world’s foremost medical and scientific institutions of the day, and Europe’s most modern manufacturing facilities. The face of the future, many believed, could be seen in Parisian leadership in such brand-new fields as motion pictures, automobile manufacturing, and aviation.

This made the disappearance of France’s most treasured artwork all the more unbearable. In the days and weeks immediately following the theft, anyone carrying a package received attention—including, at one point, a young Spanish artist named Pablo Picasso, who, four years earlier, had purchased several small Iberian stone heads that were filched from the Louvre by the secretary of avant-garde writer Guillaume Apollinaire. (Apollinaire spent a few days in jail, but Picasso had the last laugh—he used the Iberian heads as models for his Demoiselles d’Avignon.) Police at checkpoints on roads leading out of the capital examined the contents of every wagon, automobile, and truck. Fearing that the thief would try to flee the country, customs inspectors opened and examined the baggage of everyone leaving on ships or trains. Ships that departed during the day that had elapsed between the theft and its discovery were searched when they reached their overseas destinations. After the German liner Kaiser Wilhelm II docked at a pier across the Hudson River from New York City in late August, detectives combed every stateroom and piece of luggage for the masterpiece.

In the following days, from Manchester to São Paulo, the crime became front-page news. The Times of London declared, “Paris has been startled.” The Washington Post claimed, “The art world was thrown into consternation.” But perhaps The New York Times most accurately conveyed the enormity of the heist when it asserted that the crime “has caused such a sensation that Parisians for the time being have forgotten the rumors of war.” Nowhere, however, did the media cry out louder than in France itself. “What audacious criminal, what mystifier, what maniac collector, what insane lover, has committed this abduction?” asked Paris’s leading picture magazine, L’Illustration, which offered a reward of 40,000 francs to anyone who would deliver the painting to its office. Soon the Paris-Journal, its rival, offered 50,000 francs, and a bidding war was on.

The theft continued to inspire newspaper stories for weeks; any report on the case, no matter how trivial, found its way into print. One of the most popular conspiracy theories suggested that a rich American had masterminded the theft. The favorite candidate was banking scion J. Pierpont Morgan, known for his avid, not to say avaricious, collecting habits, which frequently took him through Europe on buying sprees. When Morgan arrived the following spring in the spa town of Aix-les-Bains for his annual visit, the Mona Lisa had still not been found. Paris newspapers reported that two mysterious men had come to offer to sell him the Mona Lisa. Morgan indignantly denied the account, and when a French reporter came to interview him, the American wore in his buttonhole the rosette that marked him as a commander of the Legion of Honor—France’s highest decoration. He had recently been awarded it, causing some French newspapers to speculate that he had earned the decoration by offering “a million dollars and no questions asked” for the return of the Mona Lisa to the Louvre.

Early in September, after a brief closing, the Louvre was once again opened to the public, and an even greater number of visitors than usual came to gape at the four hooks on the wall that marked the place where La Joconde once hung. One tourist, an aspiring writer named Franz Kafka, visiting the Louvre on a trip to Paris in late 1911, noted in his diary “the excitement and the knots of people, as if the Mona Lisa had just been stolen.” Some even began to place bouquets of flowers beneath the spot where the painting once resided.

What everyone wanted to know—and speculated on endlessly—was where the thief could have gone with what was probably the most recognizable artwork in the world. But the only clues were a fingerprint and the doorknob, which had been recovered by the police from the gutter outside the museum. The plumber who had opened the stairway door was asked to look at hundreds of photographs of museum employees, past and present. Every sighting or rumor about the painting’s whereabouts had to be checked out—and they came in from places as distant as Italy, Germany, Britain, Poland, Russia, the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Peru, and Japan. But by December, as the trail grew cold, the police had to shift their attention to another spectacular case. A gang of anarchist bank robbers had begun to terrorize Paris, audaciously fleeing their crimes in the first recorded use of a getaway car.

“Our Party Coming from Milan Will Be Here with Object Tomorrow”

A year after the Mona Lisa vanished, the officials of the Louvre were forced to confront the unthinkable: that she would never return. The blank space on the wall of the Salon Carré had been filled with a colored reproduction of the painting. Even that had begun to fade and curl, and many people now averted their eyes as they passed it, as if to avoid the reminder of a tragic death. So, on one December day in 1912, patrons discovered another painting hanging there: also a portrait, but of a man, Baldassare Castiglione, by Raphael.

Occasionally, stories appeared about sightings of the Mona Lisa, including one alleging that London art dealer Henry J. Duveen had been offered the painting. Duveen, however, avoided involvement by pretending that the proposal had been a joke. But another international dealer, Alfredo Geri, in Florence, was astonished by a letter he received in November 1913, more than two years after the painting had vanished. The sender, who signed himself “Leonard,” claimed to have the Mona Lisa in his possession.

Leonard said he was an Italian who had been “suddenly seized with the desire to return to [his] country at least one of the many treasures which, especially in the Napoleonic era, had been stolen from Italy.” (The fact that the Mona Lisa had come to France more than two centuries before Napoleon was born didn’t seem to dim the thief’s patriotism.) He also mentioned that, although he was not setting a specific price, he himself was not a wealthy man and would not refuse compensation if his native country were to reward him. Geri glanced at the return address. It was a post-office box in Paris.

Despite his suspicions, Geri took the letter to Giovanni Poggi, director of Florence’s Uffizi Gallery. Poggi had photographs from the Louvre that detailed certain marks that were on the back of the original panel; no forger could be aware of these. At Poggi’s suggestion, Geri invited the seller to Florence, but Leonard proved to be an elusive figure. More than once, he set a date for his arrival and then sent a letter canceling the meeting. Geri came to assume that it was all a hoax, until on December 9 he received a telegram from Leonard saying that he was in Milan and would be in Florence on the following day. The news was inconvenient, since Poggi had gone on a trip to Bologna. Geri sent Poggi an urgent telegram: our party coming from milan will be here with object tomorrow. need you here. please respond. geri. Poggi wired back that he could not arrive by the following day, but would be in Florence the day after that, a Thursday.

Geri prepared to stall. When a thin young man wearing a suit and tie, with a handsome mustache, arrived at the dealer’s gallery the next day, Geri showed him into his office and pulled down the blinds. Eagerly, he asked him where he was holding the painting. Leonard replied that it was in the hotel where he was staying. When questioned about the authenticity of the painting, Leonard replied, according to Geri’s account, “We are dealing with the real Mona Lisa. I have good reason to be sure.” Leonard coolly declared that he was certain because he had taken the painting from the Louvre himself. Had he worked alone?, Geri asked. Leonard seemed to be hiding something. According to Geri, he “was not too clear on that point. He seemed to say yes, but didn’t quite do so, [but his answer was] more ‘yes’ than ‘no.’”

Nevertheless, the discussion got down to the reward. According to Geri, the thief boldly asked for 500,000 lire. That was the equivalent of $100,000 and quite a fortune, though some newspapers had estimated the painting’s value at roughly five million dollars. Geri, holding his breath, thought that he had better agree, so he said, “That’s fine. That’s not too high.” They made a plan to meet the following day.

The next afternoon, after arriving 15 minutes late, Leonard was introduced to Poggi. To Geri’s relief, the two men “shook hands enthusiastically, Leonard saying how glad he was to be able to shake the hand of the man to whom was entrusted the artistic patrimony of Florence.” As the three of them left the gallery, “Poggi and I were nervous,” Geri recalled. “Leonard, by contrast, seemed indifferent.”

Mug shots of Vincenzo Perugia, the man accused of taking the Mona Lisa. From Rue des Archives/The Granger Collection.

Leonard took them to the Hotel Tripoli-Italia, on the Via de’ Panzani, only a few blocks from the Duomo. Leonard’s small room was on the third floor. Inside, he took from under the bed a small trunk made of white wood. When he opened the lid, Geri was dismayed. It was filled with “wretched objects: broken shoes, a mangled hat, a pair of pliers, plastering tools, a smock, some paint brushes, and even a mandolin.” Calmly, Leonard removed these one by one and tossed them onto the floor. Surely, Geri thought, this was not where the Mona Lisa had been hidden for the past 28 months. He peered inside but saw nothing more.

Then Leonard lifted what had seemed to be the bottom of the trunk. Underneath was an object wrapped in red silk. Leonard took it to the bed and removed the covering. “To our astonished eyes,” Geri recalled, “the divine Mona Lisa appeared, intact and marvelously preserved.” They carried the painting to a window, where it took Poggi little time to determine its authenticity. Even the Louvre’s catalogue number and stamp on the back checked out.

Perugia’s hotel in Florence. From Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

Geri’s heart was pounding, but he forced himself to remain calm. He and Poggi explained that the painting had to be transported to the Uffizi Gallery for further tests. The painting was re-wrapped in the red silk, and the three men went downstairs. As they were passing through the lobby, however, the concierge stopped them. Suspiciously, he pointed to the package and asked what it was. He obviously thought it was the hotel’s property, but Geri and Poggi, showing their credentials, vouched for Leonard, and the concierge let them pass.

At the Uffizi, Poggi compared sections of the painting with close-up photographs that had been taken at the Louvre. There was a small vertical crack in the upper-left-hand part of the panel, matching the one in the photos. Most telling of all was the pattern of craquelure, cracks in the paint that had appeared as the surface dried and aged. A forger could make craquelure appear on a freshly painted object, but no one could duplicate the exact pattern of the original. There could be no further doubt, Poggi concluded: the Mona Lisa had been recovered.

Poggi and Geri then explained to Leonard that it would be best to leave the painting at the Uffizi. They would have to get further instructions from the government; they themselves could not authorize the payment he deserved.

The Uffizi was an awesome setting, and Leonard must have felt overwhelmed by their arguments. How could he doubt two men of such standing and integrity? He did mention that he was finding it a bit expensive to stay in Florence. Yes, they understood. He would be well rewarded, and soon. They shook his hand warmly and congratulated him on his patriotism. As soon as he left, Geri and Poggi notified the authorities. Not long after Leonard returned to his hotel room, he answered a knock at the door and found two policemen there to arrest him. He was, they said, quite astonished.

When a reporter telephoned a curator of the Louvre to tell him the news, the Frenchman, in the middle of his dinner, said it was impossible and hung up. The following day, December 12, 1913, the museum issued a cautious statement: “The curators of the Louvre … wish to say nothing until they have seen the painting.” But when the Italian government made an official announcement confirming Poggi’s assessment, on December 13, the French ambassador made calls on the prime minister and foreign minister of Italy to offer his government’s gratitude. After disagreement within the Italian Parliament about whether the painting should be returned, the minister of public education put the argument to rest. “The Mona Lisa will be delivered to the French Ambassador with a solemnity worthy of Leonardo da Vinci and a spirit of happiness worthy of Mona Lisa’s smile,” he announced. “Although the masterpiece is dear to all Italians as one of the best productions of the genius of their race, we will willingly return it to its foster country … as a pledge of friendship and brotherhood between the two great Latin nations.”

After a triumphal tour through Italy, on January 4, 1914, the Mona Lisa resumed its old place on the wall of the Salon Carré. It had been gone for two years and four and a half months. In the next two days, more than 100,000 people filed past, welcoming back one of Paris’s most famous icons.

The Patriot

The young thief known as Leonard had been born Vincenzo Perugia, in 1881, in a village near Lake Como, in Italy. Having moved to France as a young man, the aspiring artist settled for work as a housepainter. Perugia had very briefly worked at the Louvre, from October 1910 to January 1911, and, it was discovered, even claimed to have helped craft the protective box that encased the Mona Lisa. By the time he stood trial for his crime, in Florence in June 1914, the thief’s hopes of receiving a reward for returning the painting to his native country had been finally dashed.

Alfredo Geri, on the other hand, collected the 25,000 francs that had been offered by Les Amis du Louvre, a society of wealthy art-lovers, for information leading to the return of the painting. The grateful French government also bestowed upon him the Legion of Honor, as well as the title “officier de l’instruction publique.” Geri showed what were perhaps his true colors when he promptly turned around and sued the French government for 10 percent of the value of the Mona Lisa. His contention was based on a Gallic tradition that gave the finder of lost property a reward of one-tenth the value of the object. In the end, a court decided that the painting was beyond price and that Geri had only acted as an honest citizen should. He received no further reward.

Perugia, meanwhile, was growing depressed in jail. Guards reported that he occasionally wept. But by the time his trial began, on June 4, he was again calm and self-possessed, insisting that he had acted as a patriot. Since there was no question of guilt, the legal proceedings functioned more like an inquest intended to establish the truth, if such a thing were possible. Three judges presided in a large room in Florence’s stunning Romanesque Palazzo Vecchio, which had been remodeled to provide space for journalists from around the world. (The French government never attempted to extradite Perugia.) The designer of the room had placed on a cushion, in the middle of a semicircle, a massive silver hemisphere that symbolized justice. A cynical journalist remarked that it would not be prudent to allow the defendant to sit too close to this artistic treasure.

Perugia, now 32 years old, was handcuffed when he entered the courtroom at nine a.m. Nattily dressed in a suit and tie, he smiled graciously at the photographers. Like everyone else, the chief judge was curious to learn how this apparently humble man could have carried out such an audacious crime. Could Perugia describe what happened on August 21, 1911, when he stole the Mona Lisa? Somewhat eagerly, Perugia asked if he could also explain why he had committed the crime, but the chief judge told him that he must do that later. For now, he wanted a description of the act itself.

Perugia offered an abbreviated version that contradicted both his account to Geri and the Paris Prefecture of Police’s reconstruction of the crime. He claimed to have entered the Louvre through the front door early that Monday, wandered through various rooms, taken the Mona Lisa from its place on the wall, and left the same way. A judge pointed out that, during the pre-trial interrogations, Perugia had admitted trying to force the door at the bottom of the little stairwell that led to the Cour du Sphinx. Perugia had no answer for this, and the judge did not press him for one.

It is difficult to understand why Perugia changed his story, or even why he did not tell the full truth about how he had entered and left the museum, given the fact that he freely confessed to the crime itself. Perhaps he was afraid of implicating others, but certainly the motive that he had concocted for himself—that he was a patriot reclaiming one of Italy’s treasures—would have sounded better if he had been the sole actor in this drama.

When Perugia was asked why he had stolen the Mona Lisa, he responded that all the Italian paintings in the Louvre were stolen works, taken from their rightful home—Italy. When asked how he knew this, he said that when he had worked at the Louvre he had found documents that proved it. He remembered in particular a book with prints that showed “a cart, pulled by two oxen; it was loaded with paintings, statues, other works of art. Things that were leaving Italy and going to France.”

Was that when he decided to steal the Mona Lisa? Not exactly, Perugia replied. First he considered the paintings of Raphael, Correggio, Giorgione, and other great masters. “But I decided on the Mona Lisa, which was the smallest painting and the easiest to transport.”

“So there was no chance,” asked the court, “that you decided on it because it was the most valuable painting?”

The Mona Lisa on display in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence, December 1913. Museum director Giovanni Poggi (right) inspects the painting. From Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

“No, sir, I never acted with that in mind. I only desired that this masterpiece would be put in its place of honor here in Florence.”

A judge then interrupted to play one of the prosecution’s trump cards: “Is it true,” he asked, “that you tried to sell the Mona Lisa in England?”

Accounts of the trial say that this was one of the few moments when Perugia lost his composure. He glared around the courtroom, clenching his fists as if to do battle with his accusers.

“Me? I offered to sell the Mona Lisa to the English? Who says so? It’s false!”

The chief judge pointed out that “it is you yourself who said so, during one of your examinations which I have right here in front of me.”

Unable to deny that, Perugia claimed, “Duveen didn’t take me seriously. I protest against this lie that I would have wanted to sell the painting to London. I wanted to take it back to Italy, and to return it to Italy, and that is what I did.”

“Nevertheless,” said one of the judges, “your unselfishness wasn’t total—you did expect some benefit from restoration.”

“Ah benefit, benefit,” Perugia responded—“certainly something better than what happened to me here.”

That drew a laugh from the spectators. The next day, the chief judge announced a sentence for Perugia of one year and fifteen days. As he was led out of the courtroom, he was heard to say, “It could have been worse.”

It actually got better. The following month, Perugia’s attorneys presented arguments for an appeal. This time, the court was more lenient, reducing the sentence to seven months. Perugia had already been incarcerated nine days longer than that since his arrest, so he was released. A crowd had gathered to greet him as he left the courthouse. Someone asked him where he would go now, and he said he would return to the hotel where he had left his belongings. When he did, however, he found that the establishment’s name had changed. No longer was it the Tripoli-Italia; now it was the Hotel La Gioconda—and it was too fancy to admit a convicted criminal. Perugia’s lawyers had to vouch for him before the staff would give him a room.

But most spectators had already moved on. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria had recently been assassinated in his touring car in the streets of Sarajevo. Soon the nations of Europe would be at war, and Perugia’s crime—and the ensuing hysteria—would seem rather trivial by comparison.

The Mastermind

In January 1914, months before Perugia’s trial began, a veteran American newspaperman named Karl Decker was on assignment in Casablanca. While having a drink with an elegant confidence man who went by the name Eduardo, he overheard an interesting story that would shed new light on the disappearance of the Mona Lisa. Eduardo had many aliases, but to his associates he was known as the Marqués de Valfierno or the “Marquis of the Vale of Hell.” With a white mustache and wavy white hair, he looked the part. He had, wrote Decker, “a distinction that would have taken him past any royal-palace gate in Europe.”

Decker had crossed paths with Valfierno in a number of exotic places, and the two had developed a friendship. After the police arrested Vincenzo Perugia, Valfierno commented casually to Decker that Perugia was “that simp who helped us get the Mona Lisa.” When Decker pressed him for details, Valfierno offered to confide his version of the events as long as the journalist promised not to publish them until he gave permission, or died. It was the latter event that allowed Decker to reveal what he had been told, nearly 20 years later, in 1932, in The Saturday Evening Post.

After years of success selling fake artworks, Valfierno moved his operation from Buenos Aires to Paris, where, he said, “thousands of Corots, Millets, even Titians and Murillos, were being sold in the city every year, all of them fakes.” He added people to his organization, including a well-connected American whom he refused to name. Valfierno was selective in choosing those he wished to fleece, concentrating on wealthy Americans who could pay highly for “masterpieces” that had supposedly been stolen from the Louvre.

But Valfierno and his gang never took anything from the Louvre. “We didn’t have to,” he said. “We sold our cleverly executed copies, and … sent [the buyers] forged documents [that] told of the mysterious disappearance from the Louvre of some gem of painting or world-envied objet d’art.… The documents always stated that in order to avoid scandal a copy had been temporarily substituted by the museum authorities.”

Eventually, Valfierno peddled the ultimate prize: the Mona Lisa itself, in June 1910. Not the genuine painting, but a forged copy, along with forged official papers that convinced the buyer (an American millionaire) that, in order to cover the theft, Louvre officials had hung a replica in the Salon Carré. The buyer, unfortunately, had been a little too free in bragging about his new acquisition, which prompted the newspaper Le Cri de Paris to publish an article—a year before the actual theft—stating that the Mona Lisa had been stolen.

Still, it had been a disturbing experience, one that Valfierno was determined to avoid a second time: “The next trip, we decided, there must be no chance for recriminations. We would steal—actually steal—the Louvre Mona Lisa and assure the buyer beyond any possibility of misunderstanding that the picture delivered to him was the true, the authentic original.”

Valfierno never intended to sell the real painting. “The original would be as awkward as a hot stove,” he told Decker. The plan would be to create a copy and ship it overseas before stealing the original. “The customs would pass it without a thought, copies being commonplace and the original still being in the Louvre.” After the Mona Lisa had been stolen, the imitation could be taken out and sold to a buyer who was convinced he was getting the missing masterpiece.

“We began our selling campaign,” recalled Valfierno, “and the first deal went through so easily that the thought ‘Why stop with one?’ naturally arose. There was no limit in theory to the fish we might hook.” Valfierno stopped with six American millionaires. “Six were as many as we could both land and keep hot,” he told Decker. The forger then carefully produced the six copies, which were sent to America and kept waiting for the proper time to be delivered. Valfierno said that an antique bed, made of Italian walnut, “seasoned by time to the identical quality of that on which the Mona Lisa was painted” provided the panels that the forger painted on.

Now came what Valfierno thought was the easy part: “Stealing the Mona Lisa was as simple as boiling an egg in a kitchenette,” he told Decker. “Our success depended upon one thing—the fact that a workman in a white blouse in the Louvre is as free from suspicion as an unlaid egg.” Recruiting someone—Perugia—who actually had worked in the Louvre was helpful because he knew the secret rooms and staircases that employees used.

Perugia did not act alone, Valfierno said. He had two accomplices who were needed to lift the painting, with its heavy protective container and frame, from the wall and carry it to a place where the frame could be removed. Valfierno did not name them either.

The one hitch in the plan was that Perugia had failed to test the duplicate key Valfierno ordered to be made for the door at the bottom of the staircase. At the moment he needed it, the key failed to turn the lock. While he was removing the doorknob, the trio heard footsteps from above, and Perugia’s two accomplices hid themselves. The plumber appeared but, seeing only one man in a white smock, had no reason to be suspicious. He opened the door and went on his way, soon followed by Perugia and the other two thieves. At the vestibule, the guard stationed there had temporarily abandoned his post.

An automobile waited for the thieves and took them to Valfierno’s headquarters, where the gang celebrated “the most magnificent single theft in the history of the world.” Now the six copies that had been sent to the United States could be delivered to the purchasers. Because each of the six collectors thought he was receiving stolen merchandise, he could not publicize his acquisition—or even complain should he suspect it wasn’t the genuine article.

Perugia was paid well for his part in the scheme. However, he squandered the money on the Riviera, and then, knowing where Valfierno had hidden the real Mona Lisa, stole it a second time. “The poor fool had some nutty notion of selling it,” Valfierno told Decker. “He had never realized that selling it, in the first place, was the real achievement, requiring an organization and a finesse that was a million miles beyond his capabilities.”

What about the copies?, Decker wanted to know. Someday, speculated Valfierno, all of them would reappear. “Without those, there are already thirty Mona Lisas in the world,” he said. “Every now and then a new one pops up. I merely added to the gross total.”

Characteristically, perhaps, reports of the date of Perugia’s death vary. It is known, however, that he died in France—an odd end point for a man who had once so vehemently asserted his Italian patriotism. Whatever secrets he knew about the theft were carried to the grave. The Decker account is the sole source for the existence of Valfierno and this version of the theft of the Mona Lisa. There is no external confirmation for it, yet it has frequently been assumed to be true by authors writing about the case. If indeed it is true, Valfierno had carried out the perfect crime.