Biographies of ‘homegrown’ European terrorists show they are violent nihilists who adopt Islam, rather than religious fundamentalists who turn to violence

here is something new about the jihadi terrorist violence of the past two decades. Both terrorism and jihad have existed for many years, and forms of “globalised” terror – in which highly symbolic locations or innocent civilians are targeted, with no regard for national borders – go back at least as far as the anarchist movement of the late 19th century. What is unprecedented is the way that terrorists now deliberately pursue their own deaths.

Over the past 20 years – from Khaled Kelkal, a leader of a plot to bomb Paris trains in 1995, to the Bataclan killers of 2015 – nearly every terrorist in France blew themselves up or got themselves killed by the police. Mohamed Merah, who killed a rabbi and three children at a Jewish school in Toulouse in 2012, uttered a variant of a famous statement attributed to Osama bin Laden and routinely used by other jihadis: “We love death as you love life.” Now, the terrorist’s death is no longer just a possibility or an unfortunate consequence of his actions; it is a central part of his plan. The same fascination with death is found among the jihadis who join Islamic State. Suicide attacks are perceived as the ultimate goal of their engagement.

This systematic choice of death is a recent development. The perpetrators of terrorist attacks in France in the 1970s and 1980s, whether or not they had any connection with the Middle East, carefully planned their escapes. Muslim tradition, while it recognises the merits of the martyr who dies in combat, does not prize those who strike out in pursuit of their own deaths, because doing so interferes with God’s will. So, why, for the past 20 years, have terrorists regularly chosen to die? What does it say about contemporary Islamic radicalism? And what does it say about our societies today?

The latter question is all the more relevant as this attitude toward death is inextricably linked to the fact that contemporary jihadism, at least in the west – as well as in the Maghreb and in Turkey – is a youth movement that is not only constructed independently of parental religion and culture, but is also rooted in wider youth culture. This aspect of modern-day jihadism is fundamental.

Wherever such generational hatred occurs, it also takes the form of cultural iconoclasm. Not only are human beings destroyed, statues, places of worship and books are too. Memory is annihilated. “Wiping the slate clean,” is a goal common to Mao Zedong’s Red Guards, the Khmer Rouge and Isis fighters. As one British jihadi wrote in a recruitment guide for the organisation: “When we descend on the streets of London, Paris and Washington … not only will we spill your blood, but we will also demolish your statues, erase your history and, most painfully, convert your children who will then go on to champion our name and curse their forefathers.”

While all revolutions attract the energy and zeal of young people, most do not attempt to destroy what has gone before. The Bolshevik revolution decided to put the past into museums rather than reduce it to ruins, and the revolutionary Islamic Republic of Iran has never considered blowing up Persepolis.

This self-destructive dimension has nothing to do with the politics of the Middle East. It is even counterproductive as a strategy. Though Isis proclaims its mission to restore the caliphate, its nihilism makes it impossible to reach a political solution, engage in any form of negotiation, or achieve any stable society within recognised borders.

The caliphate is a fantasy. It is the myth of an ideological entity constantly expanding its territory. Its strategic impossibility explains why those who identify with it, instead of devoting themselves to the interests of local Muslims, have chosen to enter a death pact. There is no political perspective, no bright future, not even a place to pray in peace. But while the concept of the caliphate is indeed part of the Muslim religious imagination, the same cannot be said for the pursuit of death.

Additionally, suicide terrorism is not even effective from a military standpoint. While some degree of rationality can be found in “simple” terrorism – in which a few determined individuals inflict considerable damage on a far more powerful enemy – it is entirely absent from suicide attacks. The fact that hardened militants are used only once is not rational. Terrorist attacks do not bring western societies to their knees – they only provoke a counter-reaction. And this kind of terrorism today claims more Muslim than western lives.

The systematic association with death is one of the keys to understanding today’s radicalisation: the nihilist dimension is central. What seduces and fascinates is the idea of pure revolt. Violence is not a means. It is an end in itself.

This is not the whole story: it is perfectly conceivable that other, more “rational”, forms of terrorism might soon emerge on the scene. It is also possible that this form of terrorism is merely temporary.

The reasons for the rise of Isis are without question related to the politics of the Middle East, and its demise will not change the basic elements of the situation. Isis did not invent terrorism: it draws from a pool that already exists. The genius of Isis is the way it offers young volunteers a narrative framework within which they can achieve their aspirations. So much the better for Isis if those who volunteer to die – the disturbed, the vulnerable, the rebel without a cause – have little to do with the movement, but are prepared to declare allegiance to Isis so that their suicidal acts become part of a global narrative.

This is why we need a new approach to the problem of Isis, one that seeks to understand contemporary Islamic violence alongside other forms of violence and radicalism that are very similar to it – those that feature generational revolt, self-destruction, a radical break with society, an aesthetic of violence, doomsday cults.

It is too often forgotten that suicide terrorism and organisations such as al-Qaida and Isis are new in the history of the Muslim world, and cannot be explained simply by the rise of fundamentalism. We must understand that terrorism does not arise from the radicalisation of Islam, but from the Islamisation of radicalism.

Far from exonerating Islam, the “Islamisation of radicalism” forces us to ask why and how rebellious youths have found in Islam the paradigm of their total revolt. It does not deny the fact that a fundamentalist Islam has been developing for more than 40 years.

There has been vocal criticism of this approach. One scholar claims that I have neglected the political causes of the revolt – essentially, the colonial legacy, western military interventions against peoples of the Middle East, and the social exclusion of immigrants and their children. From the other side, I have been accused of disregarding the link between terrorist violence and the religious radicalisation of Islam through Salafism, the ultra-conservative interpretation of the faith. I am fully aware of all of these dimensions; I am simply saying that they are inadequate to account for the phenomena we study, because no causal link can be found on the basis of the empirical data we have available.

My argument is that violent radicalisation is not the consequence of religious radicalisation, even if it often takes the same paths and borrows the same paradigms. Religious fundamentalism exists, of course, and it poses considerable societal problems, because it rejects values based on individual choice and personal freedom. But it does not necessarily lead to political violence.

The objection that radicals are motivated by the “suffering” experienced by Muslims who were formerly colonised, or victims of racism or any other sort of discrimination, US bombardments, drones, Orientalism, and so on, would imply that the revolt is primarily led by victims. But the relationship between radicals and victims is more imaginary than real.

Those who perpetrate attacks in Europe are not inhabitants of the Gaza Strip, Libya or Afghanistan. They are not necessarily the poorest, the most humiliated or the least integrated. The fact that 25% of jihadis are converts shows that the link between radicals and their “people” is also a largely imaginary construct.

Revolutionaries almost never come from the suffering classes. In their identification with the proletariat, the “masses” and the colonised, there is a choice based on something other than their objective situation. Very few terrorists or jihadis advertise their own life stories. They generally talk about what they have seen of others’ suffering. It was not Palestinians who shot up the Bataclan.

Up until the mid-1990s, most international jihadis came from the Middle East and had fought in Afghanistan prior to the fall of the communist regime there in 1992. Afterwards, they returned to their home countries to take part in jihad, or took the cause abroad. These were the people who mounted the first wave of “globalised” attacks (the first attempt on the World Trade Center in New York in 1993, against the US embassies in East Africa in 1998 and the US Navy destroyer Cole in 2000).

This first generation of jihadis was mentored by the likes of Bin Laden, Ramzi Yousef and Khaled Sheikh Mohammed. But from 1995 onwards, a new breed began to develop – known in the west as the “homegrown terrorist”.

Who are these new radicals? We know many of their names thanks to police identification of perpetrators of attacks in Europe and the US. More still have been caught plotting attacks. We also have all the biographical information that has been gathered by journalists. There is no need to embark on painstaking fieldwork to figure out terrorist trajectories. All the data and profiles are available.

When it comes to understanding their motivations, we have traces of their speech: tweets, Google chats, Skype conversations, messages on WhatsApp and Facebook. They call their friends and family. They issue statements before they die and leave testaments on video. In short, even if we cannot be sure that we understand them, we are familiar with them.

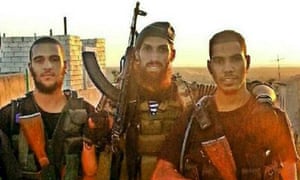

We certainly have more information on the lives of terrorists operating in Europe than we do on jihadis who leave for foreign countries and never return. But, as a Sciences Po study on French jihadis who died in Syria has shown, there are many similarities between these groups. Here I will focus primarily on Franco-Belgians, who supply most of the ranks of western jihadis. But Germany, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and the Netherlands also have significant contingents on the frontlines.

Using this information, I have compiled a database of roughly 100 people who have been involved in terrorism in France, or have left France or Belgium to take part in global jihad in the past 20 years. It includes the perpetrators of all the major attacks targeting French or Belgian territory.

There is no standard terrorist profile, but there are recurrent characteristics. The first conclusion that can be drawn is that the profiles have hardly changed over the past 20 years. Khaled Kelkal, France’s first homegrown terrorist, and the Kouachi brothers (Charlie Hebdo, Paris, 2015) share a number of common features: second generation; fairly well integrated at first; period of petty crime; radicalisation in prison; attack and death – weapons in hand – in a standoff with the police.

Another characteristic that all western countries have in common is that radicals are almost all “born-again” Muslims who, after living a highly secular life – frequenting clubs, drinking alcohol, involvement in petty crime – suddenly renew their religious observance, either individually or in the context of a small group. The Abdeslam brothers ran a Brussels bar and went out to nightclubs in the months preceding the Bataclan shooting. Most move into action in the months following their religious “reconversion” or “conversion”, but have usually already exhibited signs of radicalisation.

In almost every case, the processes by which a radical group is formed are nearly identical. The group’s membership is always the same: brothers, childhood friends, acquaintances from prison, sometimes from a training camp. The number of sets of siblings found is also remarkable.

This over-representation of siblings does not occur in any other context of radicalisation, whether on the extreme left or Islamist groups. It highlights the significance of the generational dimension of radicalisation.

As the former jihadi David Vallat has written, the radical preachers’ rhetoric could basically be summarised as: “Your father’s Islam is what the colonisers left behind, the Islam of those who bow down and obey. Our Islam is the Islam of combatants, of blood, of resistance.”

Radicals are in fact often orphans – as the Kouachi brothers were – or come from dysfunctional families. They are not necessarily rebelling against their parents personally, but against what they represent: humiliation, concessions made to society, and what they view as their religious ignorance.

Most of the new radicals are deeply immersed in youth culture: they go to nightclubs, pick up girls, smoke and drink. Nearly 50% of the jihadis in France, according to my database, have a history of petty crime – mainly drug dealing, but also acts of violence and, less frequently, armed robbery. A similar figure is found in Germany and the United States – including a surprising number of arrests for drunk driving. Their dress habits also conform to those of today’s youth: brands, baseball caps, hoods, in other words streetwear, and not even of the Islamic variety.

Their musical tastes are also those of the times: they like rap music and go out to clubs. One of the best-known radicalised figures is a German rapper, Denis Cuspert – first known as Deso Dogg, then as Abu Talha al-Almani – who went to fight in Syria. Naturally, they are also gaming enthusiasts and are fond of violent American movies.

Their violent tendencies can have outlets other than jihad and terrorism – as we see in the gang wars of Marseille. They can also be channelled, either by institutions – Mohammed Merah wanted to enlist in the army – or by sport. One group of Portuguese converts, most of whom were originally Angolan, left London to join Isis after bonding at a Thai boxing club started by a British NGO. Combat sport clubs are more important than mosques in jihadi social life.

The language spoken by radicals is always that of their country of residence. In France, they often switch to a Salafised version of French banlieue speech when they reconvert.

Prison time puts them in contact with radicalised “peers” and far outside of any institutionalised religion. Prison amplifies many of the factors that fuel contemporary radicalisation: the generational dimension; revolt against the system; the diffusion of a simplified Salafism; the formation of a tight-knit group; the search for dignity related to respect for the norm; and the reinterpretation of crime as legitimate political protest.

Another common feature is the radicals’ distance from their immediate circle. They did not live in a particularly religious environment. Their relationship to the local mosque was ambivalent: either they attended episodically, or they were expelled for having shown disrespect for the local imam. None of them belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood, none of them had worked with a Muslim charity, none of them had taken part in proselytising activities, none of them were members of a Palestinian solidarity movement, and lastly, none of them, to my knowledge, took part in the rioting in French suburbs in 2005. They were not first radicalised by a religious movement before turning to terrorism.

If indeed there was religious radicalisation, it did not occur in the framework of Salafi mosques, but individually or within the group. The only exceptions are in Britain, which has a network of militant mosques frequented by members of al-Muhajiroun, which gave rise to an even more radical group, Sharia4UK, led by Anjem Choudary. The question is therefore when and where jihadis embrace religion. Religious fervour arises outside community structures, belatedly, fairly suddenly, and not long before terrorists move into action.

To summarise: the typical radical is a young, second-generation immigrant or convert, very often involved in episodes of petty crime, with practically no religious education, but having a rapid and recent trajectory of conversion/reconversion, more often in the framework of a group of friends or over the internet than in the context of a mosque. The embrace of religion is rarely kept secret, but rather is exhibited, but it does not necessarily correspond to immersion in religious practice. The rhetoric of rupture is violent – the enemy is kafir, one with whom no compromise is possible – but also includes their own family, the members of which are accused of observing Islam improperly, or refusing to convert.

At the same time, it is obvious that the radicals’ decision to identify with jihad and to claim affiliation with a radical Islamic group is not merely an opportunistic choice: the reference to Islam makes all the difference between jihad and the other forms of violence that young people indulge in. Pointing out this pervasive culture of violence does not amount to “exonerating” Islam. The fact that these young people choose Islam as a framework for thought and action is fundamental, and it is precisely the Islamisation of radicalism that we must strive to understand.

Aside from the common characteristics discussed above, there is no typical social and economic profile of the radicalised. There is a popular and very simplistic explanation that views terrorism as the consequence of unsuccessful integration – and thus the harbinger of a civil war to come – without for a moment taking into account the masses of well-integrated and socially ascendant Muslims. It is, for instance, an unassailable fact that in France far more Muslims are enrolled in the police and security forces than are involved in jihad.

Furthermore, radicals do not come from hardline communities. The Abdeslam brothers’ Brussels bar sat in a neighbourhood that has been described as “Salafised” – which would therefore be off-limits to people who drink liquor and women not wearing the hijab. But this example shows that the reality of these neighbourhoods is more complex than we are led to believe.

It is very common to view jihadism as an extension of Salafism. Not all Salafis are jihadis, but all jihadis are supposedly Salafis, and so Salafism is the gateway to jihadism. In a word, religious radicalisation is considered to be the first stage of political radicalisation. But things are more complicated than that, as we have seen.

Clearly, however, these young radicals are sincere believers: they truly believe that they will go to heaven, and their frame of reference is deeply Islamic. They join organisations that want to set up an Islamic system, or even, in the case of Isis, to restore the caliphate. But what form of Islam are we talking about?

As we have seen, jihadis do not descend into violence after poring over sacred texts. They do not have the necessary religious culture – and, above all, care little about having one. They do not become radicals because they have misread the texts or because they have been manipulated. They are radicals because they choose to be, because only radicalism appeals to them. No matter what database is taken as a reference, the paucity of religious knowledge among jihadis is glaring. According to leaked Isis records containing details for more than 4,000 foreign recruits, while most of the fighters are well-educated, 70% state that they have only basic knowledge of Islam.

It is important to distinguish here between the version of Islam espoused by Isis itself, which is much more grounded in the methodological tradition of exegesis of the prophet Muhammad’s words, and ostensibly based on the work of “scholars” – and the Islam of the jihadis who claim allegiance to Isis, which first of all revolves around a vision of heroism and modern-day violence.

The scriptural exegeses that fill the pages of Dabiq and Dar al-Islam, the two recent Isis magazines written in English and French, are not the cause of radicalisation. They help to provide a theological rationalisation for the violence of the radicals – based not on real knowledge, but an appeal to authority. When young jihadis speak of “truth”, it is never in reference to discursive knowledge. They are referring to their own certainty, sometimes supported by an incantatory reference to the sheikhs, whom they have never read. For example Cédric, a converted Frenchman, claimed at his own trial: “I’m not a keyboard jihadi, I didn’t convert on YouTube. I read the scholars, the real ones.” He said this even though he cannot read Arabic and met the members of his network over the internet.

It probably makes sense to start by listening to what the terrorists say. The same themes recur with all of them, summed up in the posthumous statement made by Mohammad Siddique Khan, leader of the group that carried out the London bombings on 7 July 2005.

The first motivation he cited is atrocities committed by western countries against the “Muslim people” (in the transcript he says, “my people all over the world”); the second is the role of avenging hero (“I am directly responsible for protecting and avenging my Muslim brothers and sisters,” “Now you too will taste the reality of this situation”); the third is death (“We love death as much as you love life”), and his reception in heaven (“May Allah ... raise me amongst those whom I love like the prophets, the messengers, the martyrs”).

The Muslim community such terrorists are eager to avenge is almost never specified. It is a non-historical and non-spatial reality. When they rail against western policy in the Middle East, jihadis use the term “crusaders”; they do not refer to the French colonisation of Algeria.

Radicals never refer explicitly to the colonial period. They reject or disregard all political and religious movements that have come before them. They do not align themselves with the struggles of their fathers; almost none of them go back to their parents’ countries of origin to wage jihad. It is noteworthy that none of the jihadis, whether born Muslim or converted, has to my knowledge campaigned as part of a pro-Palestinian movement or belonged to any sort of association to combat Islamophobia, or even an Islamic NGO. These radicalised youths read texts in French or English circulating over the internet, but not works in Arabic.

Oddly enough, the defenders of the Islamic State never talk about sharia and almost never about the Islamic society that will be built under the auspices of Isis. Those who say that they went to Syria because they wanted “to live in a true Islamic society” are typically returnees who deny having participated in violence while there – as if wanting to wage jihad and wanting to live according to Islamic law were incompatible. And they are, in a way, because living in an Islamic society does not interest jihadis: they do not go to the Middle East to live, but to die. That is the paradox: these young radicals are not utopians, they are nihilists.

What is more radical about the new radicals than earlier generations of revolutionaries, Islamists and Salafis is their hatred of existing societies, whether western or Muslim. This hatred is embodied in the pursuit of their own death when committing mass murder. They kill themselves along with the world they reject. Since 11 September 2001, this is the radicals’ preferred modus operandi.

The suicidal mass killer is unfortunately a common contemporary figure. The typical example is the American school shooter, who goes to his school heavily armed, indiscriminately kills as many people as possible, then kills himself or lets himself be killed by the police. He has already posted photographs, videos and statements online. In them he assumed heroic poses and delighted in the fact that everyone would now know who he was. In the United States there were 50 attacks or attempted attacks of this sort between 1999 and 2016.

The boundaries between a suicidal mass killer of this sort and a militant for the caliphate are understandably hazy. The Nice killer, for instance, was first described as mentally ill and later as an Isis militant whose crime had been premeditated. But these ideas are not mutually exclusive.

The point here is not to mix all these categories together. Each one is specific, but there is a striking common thread that runs through the mass murders perpetrated by disaffected, nihilistic and suicidal youths. What organisations like al-Qaida and Isis provide is a script.

The strength of Isis is to play on our fears. And the principal fear is the fear of Islam. The only strategic impact of the attacks is their psychological effect. They do not affect the west’s military capabilities; they even strengthen them, by putting an end to military budget cuts. They have a marginal economic effect, and only jeopardise our democratic institutions to the extent that we ourselves call them into question through the everlasting debate on the conflict between security and the rule of law. The fear is that our own societies will implode and there will be a civil war between Muslims and the “others”.

We ask ourselves what Islam wants, what Islam is, without for a moment realising that this world of Islam does not exist; that the ummah is at best a pious wish and at worst an illusion; that the conflicts are first and foremost among Muslims themselves; that the key to these conflicts is first of all political; that national issues remain the key to the Middle East and social issues the key to integration.

Certainly Isis, like al-Qaida, has fashioned a grandiose imaginary system in which it pictures itself as conquering and defeating the west. It is a huge fantasy, like all millenarian ideologies. But, unlike the major secular ideologies of the 20th century, jihadism has a very narrow social and political base. As we have seen, it does not mobilise the masses, and only draws in those on the fringe.

There is a temptation to see in Islam a radical ideology that mobilises throngs of people in the Muslim world, just as Nazism was able to mobilise large sections of the German population. But the reality is that Isis’s pretension to establish a global caliphate is a delusion – that is why it draws in violent youngsters who have delusions of grandeur.