His cap is bleached as white as the bones of a Saharan camel. Is the romance of the French Foreign Legion a cult of death?

What comes to mind when you think of the French Foreign Legion? Most likely men struggling through the desert in heavy blue coats and white peaked caps. Men who joined up after a lifetime of crime, fighting valiantly, then leaving the Legion to become tough, faceless mercenaries trading on their background, or else dying in the mud of Dien Bien Phu as the last choppers leave for La Belle France.

The reality is different. In its first version, the Legion was seen as a rough mercenary force that guaranteed immunity from criminal prosecution, as well as a new life and French citizenship. In its second incarnation, the Legion became a sort of substitute family. Now in its third, the official image of the Legion is of an elite fighting force, to be compared with the British SAS or the US Navy Seals. Today, legionnaires are much more than a band of mere ‘expendables’.

The modern Legion still has a few things in common with its previous incarnations. There remains an emphasis on marching (to enter, you have to complete several hikes in full kit, ranging from 50 to 120km) and the men who join are still keen to fight. The wages, though, are now quite good, especially if you see duty in a combat zone. Even the most basic pay of a recruit is €1,205 a month, which, considering there are no bills or food costs, is nothing like the five centimes a day it was in the 19th century. Then, a legionnaire could afford wine or tobacco, not both, and certainly no other luxuries.

Young men still queue to join up in great numbers. Several thousand apply per year, and some 80 per cent are rejected – the Legion doesn’t accept anyone wanted by the police or with a serious criminal record, though misdemeanours and petty crimes are still acceptable. The modern Legion is around 8,000-strong and needs only 1,000 new recruits each year to replenish the ranks. The average recruitment age is 23. In recent times, 42 per cent of recruits come from eastern and central Europe, 14 per cent from western Europe and the US, and around 10 per cent from France. Around 10 per cent come from Latin America and 10 per cent from Asia. These young, rootless men swear their allegiance not to France, but to the Legion itself. It is their only loyalty.

The Legion is composed of several branches: engineers, paras, armoured cavalry, infantry, and pioneers. The paras are based in Calvi on the island of Corsica (they are still not trusted to be on mainland France after a coup attempt in 1961). Other arms have been garrisoned in French Guiana and the United Arab Emirates. The Legion saw service most recently in Mali, where they helped restore the government against insurgent Al-Qaeda forces.

Recruits must present themselves at one of several centres in France. If this pre-selection goes well, it’s on to Aubagne, a small town about 20km inland from Marseilles on the Mediterranean. There follows one to two weeks of selection where numerous mental and physical tests are taken. The minimum age is 17.5, the maximum 39.5. There are no educational requirements.

Exhausted legionnaires in a truck following a night of training and only three hours sleep. Nimes, France, August 2015. Photo by Edouard Elias.

Once they make it through selection, recruits sign a five-year contract and are then shipped to ‘the farm’ in the Pyrenees for six weeks of hellish training which further weeds out the unsuitable. Though probably not as tough as SAS selection in the UK, it certainly involves more cleaning, marching, singing and discipline – much more. It is accepted that hard discipline is the only way to weld men from such disparate origins into a single fighting unit. The Legion allows officers to strike the men in a routine manner. The method is age-old and simple: break the man, remove his old allegiances, then give him a new family.

In this new family, recruits are also allowed to choose a new name – the name by which they will be known ever after. And so, by the end, they have become someone new, with a new country and a new identity. Indeed, this is the most obvious pull the Legion has for men: a new life. This life, however, is wrapped up in a world that honours death.

The initial five years can be renewed at the end of service. In either case, legionnaires have the option to take French citizenship after three years – an attraction for those who would pay dearly for a European passport. A longstanding tradition of the Legion is that any legionnaire wounded in action automatically gets his citizenship, whether or not he completes his service, becoming ‘Français par le sang versé’ (French through spilt blood).

The reasons modern recruits give for joining can seem prosaic. Gareth Carins, a former quantity surveyor, turned down the British Army in favour of the Legion. ‘The truth was, I liked the army,’ he writes in Diary of a Legionnaire (2007). ‘I liked hill-walking, I liked travelling, and I was looking for an adventure.’ He reports that people regard his justification with ‘a look of disbelief and even disappointment’ – and rightly so, since the mystique of the Legion can’t be so easily captured. The one thing Carins doesn’t mention is death, but death is close to the heart of the Legion’s attraction.

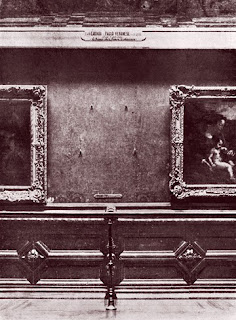

In this, it differs from the standing armies of other modern countries. Joining the British or US army involves swords and salutes on the parade ground, but the Legion’s inaugural ceremony in Aubagne leaves no doubt that this organisation cleverly manipulates the death wish of many. At the Legion’s tomblike headquarters there is a shrine: a wooden prosthetic hand that once belonged to Legion Captain Jean Danjou, who died in Mexico in 1863 defending a road for a long-forgotten cause. Around the roped off hand-shrine hang placards inscribed minutely with the names of the dead – all 40,000 of them, dating back to the Legion’s inception in 1831. The message is clear. Sacrifice is essential but you will not be forgotten.

Death-loving nihilism is not the sole motivation, of course. Camaraderie, adventure, danger, the desire to prove oneself all play their part too, as with any army. And, perhaps more than most regular armies, love affairs gone wrong propel many into the arms of the Legion. When the British author Douglas Boyd interviewed a jungle warfare instructor in Guiana about his reason for joining the Legion, he was told: ‘Histoire de nana, le plus souvent.’ (‘Girlfriend trouble, mainly.’) Romantic by nature, they seek a romantic solution by sacrificing themselves to the masculine fantasy of the Legion.

The romance of the desert was cross-fertilised with that of the runaway convict-turned-mercenary

The cap legionnaires wear, called the kepi, is bleached as white as the bones of a Saharan camel. It stands for Algeria, the Legion’s first home. With the French invasion of Algeria in 1830, there was a need for a force to pacify the country. There had been mercenary forces in the French Army before, but they had been organised along a national basis. One exception was the Hohenlohe regiment, largely staffed by Germans but including men of all nationalities. This force, raised in 1815 after the defeat of Napoleon when France was in disarray, was disbanded in 1831, its foreign troops incorporated into the newly formed French Foreign Legion that same year. So a certain amount of German DNA entered the Legion, and there remains a sneaking regard for German military prowess. Indeed, after both the First and the Second world wars, Germans formed the majority of the Legion’s strength.

The slow and brutal colonisation of Algeria during the 19th century earned the Legion its reputation for toughness and expertise in the desert. It was here that the routine use of daily 40km marches made the Legion the fastest-moving infantry strike force then in existence. The Legion were military innovators and had the quickest system of infantry movement prior to motorised transport. Two men would share a mule that carried their kit. One would walk fast at its side while the other rode. After a few kilometres, they would change places. With this system, the legionnaires could travel 70 or 80 km a day with full kit, just as fast as Bedouin raiders with their camels.

When France moved into Tunisia in 1881, and into Morocco in 1911, the Legion followed with its desert experience. The Saharan period is formative for the Legion. The romance of the desert was cross-fertilised with that of the runaway convict-turned-mercenary, creating an occidental counterpart to fellow desert nomads, the Tuareg. It is this romance that attracted not just former criminals but many well-born men to their ranks, including King Peter I of Serbia, Prince Aage of Denmark, Crown Prince Bao of Vietnam, Louis Prince Napoléon VI and Louis II Prince of Monaco. Writers and artists who have been drawn to the Legion’s ranks include the novelist Arthur Koestler, the First World War poet Alan Seeger, the composer Cole Porter and the film director William Wellman.

But the romance of the desert was not what Erwin Carlé discovered when he enlisted in 1905. Born in 1876 in Germany, Carlé had worked in the US as a cowboy and a journalist before joining up. His memoir In the Foreign Legion (1910), published under the pseudonym Erwin Rosen, portrays the traditional Legion in its toughest era, and was one source for the classic novel Beau Geste (1924) by P C Wren. For Rosen, however, the Legion ceased to be interesting and fun once he ran out of money for ‘extras’ such as wine and good food.

Rosen describes how a new recruit’s bed would be placed between two older recruits who’d teach him the ropes. If he bought them a few bottles of wine, he learned even faster. All his kit had to be folded into a ‘pacquet’ ready to be packed in a rucksack. There were no wardrobes for the legionnaire, and no privacy since he lived in a dormitory with 20 other men. Yet Rosen reports that there was barely a raised voice and no curses when the recruits were taught how to handle their weapons. Likewise, when marching, no legionnaire was told off for being sloppy or wearing his kit strangely, as long as he marched 40 km in eight hours, with five minutes’ rest every hour. While the recruits eased off their 50-kg packs to rest, the old-timers simply lay flat with their packs underneath. It saved time not undoing the straps, time that could be spent resting.

The Legion Rosen describes is one of endless toil. When not marching or training, they were required to clean and do ‘corvée’ duty: basically any dirty job required by the colonial administration in Algeria. At one time, Rosen had to clean the sewers of the local prison, and was rewarded with the jeers of the Arab population: only a legionnaire was considered low enough for this filthy job. Rosen also notes that most of the roads in North Africa were built by the Legion, a handy hard-working force that was then among the cheapest in the world.

Harsh treatment was not seen as unjust: any man who couldn’t keep up would be killed by the Arab forces

Why did they put up with this? Many didn’t and talk of deserting was common, but without money it was difficult to escape. It became rather easier to desert after 1962, when the Legion shifted its headquarters from Sidi Bel Abbès in Algeria to Aubagne; Carins tells of a modern-day American who left during training and headed over the Pyrenees into Spain. If caught, he would have been sentenced to military prison, but he made it home. The kind of official manhunt that would have been sanctioned by desertion 100 years ago is far more lacklustre today. The fact is, the modern Legion has enough keen recruits not to care too much if some run away.

In the past, strong discipline merged into punishment. If a man fainted on a march, he’d be tied to a pole sticking out of the side of a wagon. His arms would be supported, but if his legs couldn’t perform a walking action, he would be dragged along, burning a hole in his boots and feet. This harsh treatment was not seen as unjust since any man who couldn’t keep up would be killed by the Arab forces that often tailed the expedition.

After the Mexican civil war of 1857-60, and as an interlude from pacifying the North African colonies, the Legion was sent to help install Maximilian, the brother of the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph, in Mexico. There were other troops also on loan to the insurgent regime including British Royal Marines, Austrian footsoldiers and even 447 Egyptians. But it was the French who stayed longest, until 1867, and did most of the fighting. Oddly enough, one of the few remaining influences of the Legion’s time in Mexico is the widespread acceptance of the French word for marriage to describe wedding musicians: the mariachi band.

The story of the Battle of Camarón on 30 April 1863, when Captain Danjou lost his life, has become the stuff of legionnaire legend. Surrounded by 3,000 Mexicans, Danjou and 64 of his men were given the chance to surrender. Danjou, however, knew that if he held up the Mexicans, a vital convoy of supplies would have time to get through to his men. So there would be no surrender. Down to their last cartridge, the final six legionnaires standing made a bayonet charge. Somehow, three of the six survived (with hideous wounds) and were protected by a merciful Mexican officer impressed by their bravery. Even then these three gave in only when their terms were met: that they kept their empty rifles and could give an honour guard to escort the remains of Captain Danjou. But not all his remains. In a macabre, comic twist, his wooden hand was somehow overlooked. After prolonged negotiation, it was later bought back by the Legion from a Mexican farmer who had found it but was reluctant to part with it. This is the wooden hand enshrined in Aubagne, where each new legionnaire is inducted, and where they say a final goodbye upon completing their service. The day of Danjou’s death is still celebrated every 30 April as Camarón Day.

The First World War, in which one in three French men of military age died, saw the Legion employed on many fronts fighting the Germans and Austro-Hungarians. Germans who were in the Legion were kept in Algeria for fear they might desert. The rest fought. The Legion, along with the Moroccan Division, were the most decorated French unit in the 1914-18 conflict. They fought on every front, including Gallipoli, but, when the war ended, their numbers were so depleted there was talk they ought to be disbanded despite their gallantry.

This was a crucial moment: the Legion needed to reinvent itself or die (echoing its mantra ‘march or die’), and a certain Colonel Paul-Frédéric Rollet came to their rescue. Short, slight, well-bearded, and with a penchant for wearing rope-soled espadrilles not boots while marching, Rollet understood that, instead of offering a sanctuary for runaway convicts, legionnaires needed a new myth of belonging and self-sacrifice. The Legion has won many battles since its formation but is known, really, for its marvellous defeats: at Camarón in 1863 and at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam in 1954 (where another one-armed officer, Colonel Charles Piroth, showed extreme bravery before killing himself with a grenade).

Rollet was a military genius who understood the inner symbolism of such things as heroic defeats, odd uniforms and lost limbs: Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart, one of Britain’s most decorated officers; José Millán-Astray, founder of the Spanish Foreign Legion; and Admiral Horatio Nelson himself were all missing hands or arms. Suggestively, Paul Rollet went into battle with just a rolled umbrella. He believed that a commander showed lack of faith in his men if he needed to be armed, and besides, it distracted from his real task of inspiring his soldiers to fight. That Rollet seized on the heroic defeat at Camarón is no accident: men brought up to accept death and mutilation as the price for never being forgotten by their uber-family (the Legion) are stronger than those bribed with the comforting notions of victory and glory. Rollet knew that an army doesn’t march on its feet, or even its stomach. It marches on the stories it tells itself. So he made sure that the Legion was full of traditions and stories and rituals. He also turned a few marching songs into full-blown anthems. However tough, legionnaires must learn to sing with gusto the songs of former warriors. Other armies don’t really do this, nor do the officers bring the men breakfast once a year (on Camarón Day, of course). This action alone mimics a family in its concern. Every Legion memoir (and they are legion), however much it complains of bullying or incompetence, mentions with heartfelt gratitude the songs and traditions imbibed alongside the forced marches.

One calls ‘Cuckoo!’, then dives for cover. The other shoots. The game ends with death, severe injury, or empty guns

Having fought through the First World War, Rollet had seen the mechanised future of warfare, and realised that men respond badly when treated like machines. He’d watched the French Army mutiny in 1917 and had even used his legionnaires to put down such an insurrection. This was a French Army that had been treated as cannon fodder for the great machine of death that was the Western Front. Rollet would go the other way. On the Legion’s 100th anniversary in 1931, and the first Camarón Day, he ordered that the infantry be led by bearded pioneers carrying immense axes. It was a quirky refusal to put guns on show but he knew that discipline and morale were more important than mere firepower. Not that they didn’t have that, too. Rollet expanded the Legion into infantry, cavalry and engineers. Too many French boys had died in the First World War, so from now on foreigners would defend France’s colonies. He had them posted in Fez and Marrakech in Morocco, in Sidi Bel Abbès in Algeria, as well as in Tunisia, Syria and Indochina. Between the wars, the Legion was at its greatest numbers, counting some 33,000 men.

Astutely, Rollet maintained the early German connection by making official the slow, 88-steps-a-minute march of the old Hohenlohe regiment. He maintained the desert connection with the official headwear, the white kepi, with its back flap as protection against the sun. But perhaps Rollet’s greatest legacy was to put in place the elements necessary for the Legion to later transform from yet another mercenary colonial force to an elite fighting unit.

But in Rollet’s day, that elite quality was still a few years away. The interwar, uber-family Legion is perhaps best known for the games they created. Russians who joined taught bored fellow legionnaires to play Cuckoo. Two men with loaded revolvers enter a cellar or darkened room. One calls ‘Cuckoo!’, then dives for cover. The other shoots. Then he calls cuckoo and the other fires. The game ends with either death, severe injury, or both revolvers empty. Another lark was Buffalo, in which each participant drinks a bottle of vermouth and then charges head-down at his opponent with hands tied behind his back, with things settled literally by cracking heads. If both are still standing afterwards, another bottle is drunk, and another head-on collision arranged. Usually two bottles, occasionally three, were consumed per man before a cracked skull or severe concussion decided the duel.

In the Second World War, the Legion fought against the invading Germans. After France fell, the Legion split: some remained loyal to Vichy, others sided with Charles de Gaulle and Winston Churchill. These two sides of the Legion actually faced each other briefly in Syria, before the Vichy forces capitulated and joined the Free French.

One legionnaire who served in Syria and later North Africa was Susan Travers, the only woman ever to be officially recognised as a full Legion member. The bilingual daughter of a British Navy officer who grew up in France, Travers was 32 when she unofficially joined. First a nurse and then an ambulance driver, she became the mistress of several Legion officers, ending up with the commander General Marie-Pierre Koenig. Travers demonstrated real courage under fire on numerous occasions. She was the only woman allowed in the defensive ‘box’ perimeter at Bir Hakeim, a battle that ended with the Legion making a heroic stand, and breaking out under cover of darkness to escape capture. It was Travers who drove the two commanding officers – both of whom had been her lovers – and the car suffered only 11 bullet holes and ruined shock absorbers. They let her drive not because it was her job, but because she was the coolest behind the wheel.

After the Second World War, many of the Legion’s former enemies, especially German soldiers, joined up. That some had served in the SS is a rumour many legionnaires like to promote but one that’s hard to believe. Members of the SS had their blood group tattooed on their arm, and even those with the tattoo removed would have found post-war recruiters far from sympathetic. But there were plenty of ex-Wehrmacht soldiers to swell the forces of the Legion in its next two conflicts: Indochina and Algeria.

Indochina between 1946-54 should not be mentioned lightly when the Legion is concerned. Often called the Michelin war (after the giant tyre company that stood to lose its immense rubber plantations if the Communists won), the Legion did its mercenary best, despite being given a hopeless task and incompetent leadership under General Henri Navarre, the architect of the Dien Bien Phu fiasco.

At Dien Bien Phu, where the Camarón story was read out before the final assaults by the overwhelmingly superior numbers of Vietnamese, the Legion showed that they could still die – but for what? France was already committed to pulling out of Vietnam, and was simply using military action to gain better terms. In the late 1950s and early ’60s in Algeria, the protracted and bloody civil war mimicked the previous bloody conflicts with Arabs. This time it was decolonisation on the cards.

France was split about Algeria, though the majority favoured pulling out. Four former generals of the French Army thought otherwise, and staged a coup against De Gaulle in 1961. The elite 1st parachute regiment of the Legion were sent to capture Paris. De Gaulle went on radio and television appealing to the nation to side with him against the revolt – and succeeded. The 1st paras were disbanded, though, strangely enough, not really in disgrace since a legionnaire swears allegiance to the Legion and not to France. In following their superior’s orders to effectively mutiny against the government, they were not acting dishonourably but according to their code. And when the troops made their final march before disbanding, they sang the Édith Piaf classic ‘Non, Je, ne regrette rien.’

To outsiders, it looks a little strange. All that discipline and marching – and then ending up dead

The coup attempt brought to the surface the troubled relationship between France and its Foreign Legion. The French admire it and yet don’t quite trust it. Another reinvention was required. This time, the solution was truly bold: to turn the Legion into an elite force, a strike force, the kind that could easily put down a coup, or stage one in another country. The undisgraced 2nd Para became the ‘Young Lions’ of this newly created force.

Elite fighting forces are a serious attraction to young men. And the Legion, unlike many special forces, gets to fight a lot. Death and elitism are a heady cocktail. Since the late 1960s, the Legion has fought with distinction in Chad in 1969-71, in Zaire in 1978, and been a peacekeeping force in Lebanon in the early 1980s. During the First Gulf War in 1990-91, they served to protect one arm of the coalition forces and received very light casualties. In 1992, they were back in old Indochina in Cambodia, and also in Somalia. In 1993, they were in Bosnia, and Rwanda in 1994. In this century, they have served again in the Ivory Coast in 2003, and Chad in 2008. In 2013-14, they helped to rid Mali of the politicised Islamic extremists that took control of Timbuktu – a return to their romantic desert roots.

Ex-legionnaires are rather touchy on the subject of their motivation. They naturally distrust anyone who hasn’t had their experiences. To outsiders, it looks a little strange. All that discipline and marching – and then ending up dead. That they are men who love fighting is only half the story. Even the desire to prove oneself as manly and tough cannot account for the continued fascination for this army of foreign mercenaries who celebrate not victory but an honourable death. One has to go further, and look at the Samurai tradition of Japan, where an almost erotic interest in death runs alongside a more workaday nihilism. According to the 18th-century Samurai manual the Hagakure: ‘A real man does not think of victory or defeat. He plunges recklessly towards an irrational death. By doing this you will awaken from your dreams.’